|

|

| Prozit! (she refused to send it) Anda Kļaviņa, Art Critic Humour and irony in the photography and life of Uldis Briedis during the Soviet period | |

| Uldis Briedis (born 1940) worked in Liepāja from 1966 until 1979 as a photo correspondent, initially at the Liepāja district newspaper Ļeņina ceļš, and later at Liepāja city newspaper Komunists. His apartment on Jāņa iela, which was commonly known as Vāgūzis, was a creative bohemian meeting place all through those years. The informal get-togethers, besides involving deep discussions and the use of alcohol, included music-making (free improvisation also) and poetry readings as well as elements of theatre and performance not unlike visual art installations. These undertakings, this ‘fooling about’ were of a spontaneous nature, without artistic intent. These events were often oriented towards the provocation of state institutions and the lampooning of official discourse. In these events, Briedis acted both as the ideological initiator and implementer, as well as their documentarist. At times the events at Vāgūzis gathered together intelligentsia from Liepāja and Latvia of all generations: film and theatre actors, directors, cine-operators, poets, writers – both the officially recognized and the unpublished, pop performers, musicians, former political prisoners, journalists, artists, photographers and others. The most frequent visitors to Vāgūzis were the poet Olafs Gūtmanis, journalists Ingvars Leitis and Andžils Remess, as well as Liepāja’s theatre actors and those who moved in Latvian cinema (especially documentary film) circles. The figure of photographer Uldis Briedis and Vāgūzis were interesting phenomena in the context of the Soviet Latvia cultural landscape, as they personified a Soviet person’s attempts to live a creative and positively meaningful life, sometimes contrary to the aims of the Soviet state, sometimes – in accordance with them, but mostly maintaining an attitude that did not fall into any polarly opposed “oranges and lemons” category. It legitimized those many lives of Soviet state citizens, in which creativity developed in the unique symbiosis between official discourse and individual lifestyle (meaning by this ethical and aesthetic principles), but which, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, have been denounced as corruptive.(1) The life story of Briedis is a story about the possibility of an authentic life (not without its darker side), independent of the existing political system. In its own way it is only a coincidence that the main hero of this life is a photo reporter by profession, one who not only diligently carried out his job, but also prolifically documented the other parts of his life, as a result providing a very diverse kaleidoscope of Soviet life and allowing us, too, to view this material in an artistic context. | |

Another example of a Soviet person teleporting. A spontaneous performance at the Ciecere River in the early 1980s together with Felikss Zvaigznons, a colleague from the publication 'Padomju Jaunatne' ('Soviet Youth'): "We dragged a bed into the river and pretended that we lived in the river." | |

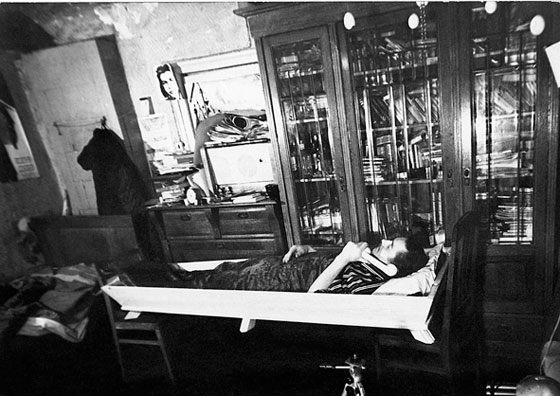

| By day – taking photographs of exemplary factory workers, official meetings and other subjects reflecting the building of communism, by night – Riflemen’s stories, making music in the spirit of pre-war Latvia, poetry and fooling about. Uldis Briedis’ photography of the Soviet period speaks of two different worlds which existed in parallel in the Liepāja of the 1960s–1970s. Vāgūzis itself – a small two-room ground floor apartment on Jāņa iela (the building no longer exists) was a journey in time and space. The apartment’s focal objects were a wooden coffin and a wooden cart, which were used both as a table and bed in turn, beside them a collection of ship’s bells, and on the floor – a millstone. In the apartment there was also an oak secretaire which Briedis had taken from some administrative institution before it was thrown out, and a large wooden table with benches on both sides, which he had specially commissioned from a local carpenter. I lived together with two musicians, Šrāders and Ronis – formerly musicians in a famous Liepāja tavern, who after the war continued to play in the Liepāja Musical Theatre Orchestra. They told me of their experiences in pre-war Latvia. Ronis was plump and a teetotaller. Šrāders was etiolated and a heavy drinker. Ronis had a violin collection – there were 12 of them hanging on the wall. He made extra money repairing violins. Meanwhile Šrāders made extra cash by copying sheet music. He always had classical music playing. When he’d been drinking he used to talk about composers, what kind of mood they’d been in when they’d composed... It was a whole different world! Having listened to it for ten years, I came to love classical music very much.(2) In Liepāja I met many interesting people from the 1930s. Old mariners who had graduated from the K. Valdemārs Sea School – the real ones, intelligent people. There were Latvian Riflemen, at that time still in their prime. The influence of that generation was enormous. I regret that at the time I didn’t think of turning on a tape recorder: on occasion we talked about olden days for eight hours during the night. There was a Krauze from Aizpute, formerly a reconnaissance commander – he had stories to tell! Such lively language as you’d never find in a book. So many preconceptions about the Latvian Riflemen and pre-war Latvia were destroyed. Although unique in its individual features, this space is reminiscent of many other Soviet era private spaces that their inhabitants had transformed into a territory of dreams and imagination, in which ideals and values unconnected with the official politics of the Soviet regime, but not necessarily in opposition to it, could be manifested. They were groups of people who had their own knowledge, codes and meanings, and who together generated the greatest variety of “elsewheres”. Poetry, religion, early languages, literature, Western rock music. Each could select the era in which they wished to live, characters to embody. Briedis’ world was that of pre-war Latvia: in the pictures one can see fishermen, decathlete Zigurds Pakalns, writer Egons Līvs, Teodors Cukurs (brother of the pilot Herberts Cukurs), former political prisoner Jānis Kadiševskis – personalities who at that time still actively contributed to the atmosphere of Liepāja. At this time bard Haralds Sīmanis, Ingvars Leitis (prior to the founding of the Katedrāle group), Arvīds Ulme, Jānis Ošenieks, Olafs Gūtmanis and others played or recited their latest or spontaneously created musical compositions and poems chez Briedis. Parties and revelry with the participation of Liepāja theatre people and cinema actors, directors and others allowed one to be “teleported” to other pastures of freedom (admittedly, not without serious helpings of alcohol). According to anthropologist Alexei Yurchak from Berkeley University, California (Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More, Princeton University, 2006), the existence of such a space emerged from an internal mutation of the existing regime. After Stalin’s death, markedly standardised, hyper-normalized fixed forms of Soviet ideological discourse (in language, in visual propaganda, in the routine of daily life) over time became ever more distanced from the actual reality of the Soviet state and the Soviet person. The Soviet person lived a completely different life from the authoritative discourse. Creativity, which wasn’t permitted or was restricted in the official space, moved out to the rest of the living space, allowing other time-spaces, social relations and meanings to develop. Yurchak called this the deterritorialisation of the Soviet system: the Soviet person had one foot in Soviet reality, and the other – elsewhere.(3) Here it is important to stress that existence elsewhere was not always in opposition to the official ideology, to be elsewhere and at the same time here (in Russian the word for this is vne) was a “logical” component of Soviet life. | |

Portal to other dimensions of time. The only thing in Uldis Briedis' living room that interested the Soviet security authorities was the large wooden table. "You have a long table - who sits at the table?" they asked. Death was the point at which the sphere of influence of this authoritarian regime ended. Death was the zone of freedom, and the coffin - a symbol for the parallel lives of Soviet person. 1976 | |

| At Vāgūzis they were one’s own kind of people, who reflected on the conditions of Soviet life but at the same time made use of the opportunities provided by the system: creating careers, travelling around the Soviet Union, using their connections to create a backing network and being conscious of what the system asked of them for this to be possible. The presence of one’s own kind made Uldis Briedis’ work at various Liepāja newspapers and later – at Padomju Jaunatne (‘Soviet Youth’) pleasant and creative. He took the liberty of slightly “touching up” official photos, for example, making the Latvian SSR Council of Ministers Meeting Hall darker to emphasize the gloomy atmosphere prevailing there, or “placing” the local Communist Party leader in a picture so that the window frame behind him formed a cross. The main thing was to stick to the required form, and then unbelievable things would go through. One evening, we were sitting with the deputy editor, the late Leons Buls, who was also the newspaper’s chief of Party affairs. We started talking about the war, about the Legionnaires, and decided to play a joke on Egons Līvs, who had been in the Legion and later in a prison camp. We placed an advertisement in the paper: “The last edition of writer Egons Līvs’ book, ‘Soldiers are not reproached’, has been released.” The typesetter had already gone home and we put together the text ourselves, in block letters too: SOLDIERS ARE NOT REPROACHED. The next day Egons was scared rigid, and we were pretty shaken ourselves. The editor was very worried. But nobody had noticed. That’s how it was in Soviet times – sometimes you got into trouble for a trifle, but at other times you got away with unbelievable things. The Soviet state demanded an accurate reproduction of formal expressions of authoritative discourse: parades, elections, meetings and gatherings, examinations, the way public texts were drafted etc. These texts and rituals didn’t have to be taken literally – in keeping with how accurately reality was described, it was important to repeat them precisely. In their invariability and predictability they were the only things which created a sensation of the enduring nature of the Soviet state. One’s own kind were people who recognized the necessity of carrying out ideological rituals, so that they in turn could live a “normal life”, undisturbed. This understanding about the fulfilment of the discourse requirements of the powers that be created a special solidarity, with its own internal ethical code.(4) “My Liepāja collective often rescued colleagues. One supported the other. Everyone understood me.” Once Uldis Dumpis knocked at my window at six o’clock in the morning. I let him in and gave him the poem ‘Pamatlikums’ by Jūlijs Vanags to read, recently published in [the literary magazine] ’Karogs’. He was hanging on to the big bell in the middle of my room and reading, but getting nowhere, because he wanted to laugh. And each time he laughed, the bell rang, at six in the morning... My friend, artist Aldis Kļaviņš, was at the creative house at Palanga. I sent pictures to the manager of the institution in which Aldis looked like a prisoner, with an accompanying text that he was an escaped criminal. The manager understood the humour and in a serious tone of voice had invited Aldis into his office for a “discussion”. I used to call up any random number and talk to people. Once I telephoned someone’s apartment and a woman answered. – Good day. I’m from the housing department, team leader of the parquet installation team. Tell me, I can’t really remember – do you have parquet in your apartment or not? – No, we don’t. – Ah, then I’ve rung the right number. We intend to install parquet in your apartment. I do have a request: could you free the apartment of furniture? We work very quickly – if the room is empty, we’ll lay the parquet in a couple of hours. – Thank you for your call! I’ll do that! She believed me. After that she most likely searched around the housing department angrily looking for who did this. Episodes which may seem simple boyish tomfoolery today, in the 1960s / 1970s formed a part of the particular relations of Soviet official discourse. The growing gulf between the formal dimension of official discourse and its actual meaning promoted the development of a culture of irony and the absurd. Refusing to draw a clear line between reality and performance, seriousness and humour, support and opposition, meaning and tomfoolery, life and death, this humour imitated the paradoxical consequences of mutated authoritative discourse.5 When Soviet symbols and everyday situations were the subjects of this humour, their meaning was revealed to be open, absurd, unpredictable or simply nonsensical. At the end of the 1970s and in the 1980s, the practice of such humour, in the context of art, was developed by Mitki in Russia and Nebijušu sajūtu restaurēšanas darbnīca [Workshop for the Restoration of Unprecedented Feelings] in Latvia. Having picked up on the system’s internal inconsistencies, Uldis Briedis and many of his contemporaries, just like little children who have discovered the joy of the game, indulged in creative relationships with it all, in every way possible. Following the formal instructions of the discourse, but playing around with the point of it, from passive characters – heroes, they became authors who assigned new meanings. A banquet was held at the Liepāja Meat Processing Works in honour of the visit of a Central Committee member, Navy Commander-in-Chief Gorshkov. Very high up: he was one of those who stood on the Mausoleum during celebratory parades. All the Liepāja heavyweights and the Navy security officers were taking part. That year you basically couldn’t find meat in the city’s shops, but here the tables were groaning. They sat down to eat and I thought: “Hang on, I want some too”, and sat down in a free place, calmly dining together with them. I asked someone to take a photo of me eating pork cutlet with them. I wanted my wife to receive a greeting on her name day from the most distant outpost in the USSR – Petropavlovsk in Kamchatka. I sent a card there with a false address calculating that usually they’d hold the letter at the post office for a month if they couldn’t locate the addressee, and then send it back. In this way I created a long journey for the card –12 thousand kilometres round trip – that’s half a hemisphere in length. And the main thing, it arrived almost to the day on the right date. Once we decided to engage in ķekatas [mummery]. One of us put a German army helmet on his head (the helmet had been lying around in my apartment), I was half-naked and wrapped a fishing net around myself, an actor placed a saucepan on his head and, whilst singing, we stormed into the Jānītis Café. A bunch of naval officers were sitting there, celebrating Lenin’s birthday. They all shot to their feet. They blocked the door and called the police, but as for us – one, two, out the kitchen door and back to my apartment. I had a good friend who worked at the consumer association food depot. I wanted to send him up, so we put an advertisement in the paper: “Greetings to Žanis Rubess on his birthday.” All of the ladies who worked with him at the depot – very sociable and convivial – were reduced to despair that they’d let their colleague’s birthday slip by. They ran off to the shops and to the market for flowers and drinks. When Mr Rubess arrived at work everyone in the collective greeted him. But he had no idea what was going on. The effect was achieved. Once, though, a telegraph operator in Russia refused to send my telegram to my colleagues at the newspaper, as there was only one word: “Prozit!” 6 She didn’t know what it meant and was afraid of the consequences. Even though Uldis Briedis toyed around with the forms of authoritative discourse and tested its boundaries, he still didn’t stand up against it openly. That was the real difference from dissidents, who “took it seriously” – they stood up against the ideological discourse, giving it credence as a reflection of the truth, and tried to unmask the lies. In Briedis’ circle there weren’t any dissidents, and he, like other creative young people from the 1960s and 1970s (Imants Kalniņš, Māra Ķimele, Andris Grīnbergs, Zenta Dzividzinska and others) whom I have interviewed, were more inclined to distance themselves from dissidents, specifically because they spoke in the same discourse as the institutions of power. “If you took all this to heart, then you’d lose your mind. ... We didn’t complain. We laughed at the system. And in this way we made our lives a little rosier.” (U. Briedis) | |

Another music making session in Vāgūzis. Ingvars Leitis, Olafs Gūtmanis, and on guitar Jānis Ošinieks, a telephonist who composed music and wrote poetry in his spare time. The episode in which he called his classmate Māris Čaklais from the top of a telephone pole was later immortalised in Čaklais' poem: "The city where wind is born". 1976 | |

| This, however, doesn’t mean that the state security service wasn’t a frequent visitor at Briedis’ apartment and the reverse, but here, too, Briedis had his “recipe”: “I played with an open hand, talked about national issues, didn’t hide anything. When the Cheka interrogated me, I noticed that at the end they usually said: “Let’s keep this between us.” Then, one time, I realized that I should do the exact opposite: I told everyone that I met on the street that I had just come from the Cheka. It was natural that there would be informers who would take the news back. In the end the Cheka avoided me, because “that Briedis will shoot his mouth off again”. However, such frankness eventually worked against Briedis, as his acquaintances and even his friends began to think that he could only afford to make such jokes if he himself was from the Cheka – either an employee or an informer. “They called me a pushover.” And even for the ruling authorities, at one point his free spiritedness began to seem like self-indulgence. When in 1974 Briedis and [his friend] Leitis headed off for a six month journey to Latvian villages in Siberia, the state institutions stopped his reports for Zvaigzne magazine and hence the financial backing for the expedition. “We hid the trip under the clever slogan: “A cycling trip Riga–Vladivostok dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the USSR victory over fascist Germany and imperialistic Japan”. But the Cheka already knew what sort of horror stories we would get to hear there, and that’s why they put the kibosh onto it. The accounts of repressions against the Latvians were horrifying.” The travellers were supported by their friends, and it was friends also who allowed Briedis, on his return, to work as a photographer under an assumed name, Matīss Pērkons. In parallel Briedis began working at the Liepāja Museum where, under the title Latvia’s cultural and art monuments, he was able to create an exhibition of photographs about Latvia’s church building heritage. He talked the museum into letting him exhibit his collection of bells as well. The exhibition in this form could be viewed for two days – before the Commission made him remove the bells. “I didn’t even have any church bells there – just one cemetery bell, little horse cart bells, the rest were ships’ bells.” While working at the museum, in the 1970s Uldis Briedis documented how individual farmsteads of Kurzeme were being destroyed through the introduction of drainage. “Solid houses were being destroyed, sometimes together with everything they contained, avenues of linden and oak trees – it was all burned down! I have a picture of an excavator driving through an apple orchard. At that time people in the country had nothing to do. They flooded into the cities, left their homes. I realized that I had to document this irreversible historic process.” During the Soviet period Briedis did not put these pictures on display, but on his initiative the tradition of organizing an annual open-air exhibition on Jāņa iela was started up. In cooperation with the energetic Liepāja Photo Club leader Huberts Stankevičs and well-disposed people from the Liepāja Party Committee, permission was pushed through with all of the authorities. “At that time it was something unheard of – an exhibition on the street. But the street was ideal – a secluded, narrow little street, on which there were two warehouses with a large space under the roof where to hide from the rain. A beautiful old wooden log background. Very cosy. A wooden table was placed at the end of the street – there was an entry fee. In addition to exhibitions, in later years poetry days also took place. Liepāja has always been a revolutionary city – for everything.” The photography by Uldis Briedis which served the Soviet regime and the photography which reflected the world of the Soviet person organically reveal the two sides that constituted Soviet reality. Alongside the greyness and alienation of Soviet life, humanity, friendship and creativity also bloomed. Briedis’ work helps us to see this, and in the perspective on this era takes away the weighty burden of the dichotomies of power / resistance, conformism / non-conformism, lies / truth etc., urging us towards a more complicated analysis. Although exaggerated in its flamboyance against the background of the life of an average resident of the Soviet Union, Briedis’ life is an example of a person’s attempt to live a full-blooded, creative life: adapting and at the same time maintaining his own ideals and ethical code, succumbing and at the same time insisting on human respect. It is a creative, but not always a successful battle to retain manliness (courage, endurance, fraternity, justice, initiative, maybe even responsibility). They are values which were important then as they are now, and this explains the popularity of Briedis’ work and the abiding love of his fellow-citizens which he has received over the years. (1) Patrick Serot has found in research that at the end of perestroika it was politically important, especially for the intelligentsia, to emphasize that during the Soviet period their language had not interacted with the language of the state, and that only aspirations for freedom had been expressed through their mouths. Serot, Patrick: Officialese and Straight Talk in Socialist Europe, St. Martin’s Press, New York, 1992 (2) The text contains fragments from interviews Anda Kļaviņa conducted with Uldis Briedis in May, September and November 2009, as part of the research “Un citi…Neoficiālās mākslas parādības Latvijā 1964 – 1984” [‘And others… Unofficial art phenomena in Latvia 1964–1984’]. (3) A.Yurchak, pp. 76–78 (4) A.Yurchak, pp. 117–118 (5) Eda Cufer: Enjoy Me, Abuse Me, I am Your Artist: Cultural Politics, Their Monuments, Their Ruins // East Art Map, 2006, Afterall Press, London, pp. 362–370 (6) Prozit! – Cheers! (Ed. note) /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ | |

| go back | |