|

|

| Searchin’ every which way Barbara Fässler, Artist Bas Jan Ader. Tra due mondi 24.01.–17.03.2013. Mambo, Villa delle Rose, Bologna | |

| What is the drive that makes a thirty-three year old man try out his powers against Mother Nature – alone, practically with naked hands – besides nature at its most powerful? An archetypical horror scene comes to mind – the boat like a small sliver of wood is thrown back and forth in the crashing waves, until it tilts and topples over, devoured by the infinite ocean, the only winner in this struggle. We can only imagine the absurd scene on the following day – an idyll, the expanse of water as smooth as the glass of a mirror, the sun is shining, as if nothing at all had happened… Those who knew Bas Jan Ader in person speak of him as a reclusive and contemplative person. He was not much into going out with friends – they drank and smoked too much. Something always urged the young artist on, he was always speeding towards something, and driven by an internal inquietude he was always in search of something. Born in 1942 in Winschoten (the Netherlands), he was a “difficult”, rebellious teenager. He abandoned his studies at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, where he had spent half a year working on a single sheet of paper, continuously sketching, erasing and re-drawing. At the age of nineteen he hitchhiked to Morocco, boarded Neil Tucker Burchet’s yacht Felicidad(1) and eleven months later stepped out on the California coast. He first enrolled at Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles, and then he attended the Claremont Graduate School, obtaining a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in art. From 1967 to 1969 he studied philosophy at the university in Claremont, and took a special interest in the philosophers Hegel and Wittgenstein. He married Mary Sue Andersen in 1965 in Las Vegas. Bas Jan Ader’s works were created in the atmosphere of 1960s California, when West Coast conceptual art was born, with both linguistic analysis and irony having their own role. But Ader is different from other artists of the time with the existentialism of his happenings, which overshadows the comicality that might be observed at first sight. The Dutch Californian artist is considered to be one of the forerunners of Romantic Conceptualism – this term was coined by the art critic Jörg Heiser, and this is also the name of a 2007 exhibition at the Nuremberg Art Museum. Romantic Conceptualism is a movement that fuses conceptual art which Romanticism, thoughts with feelings, ideas with sentiment. What we have today of the approximately 35 works that Bas Jan Ader created in almost ten years are photographs, films or video recordings: they document his performances or installations. In them we can perceive quite a number of references to Romanticism, melancholy, and to the history of art as well. | |

Bas Jan Ader. The Boy Who Fell Over Niagara Falls. 16 mm film. 1972 Publicity photo Courtesy of the Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Bas Jan Ader Estate, Mary Sue Ader Andersen and Patric Painter Editions | |

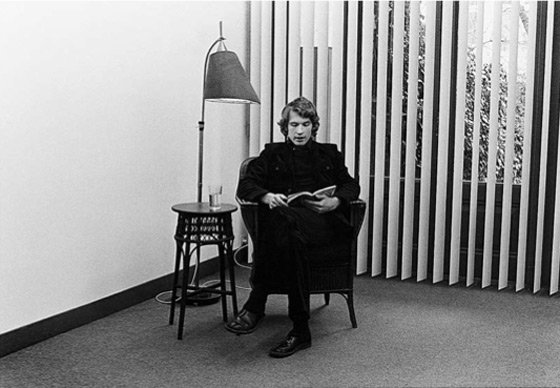

| The colour photograph Farewell to Faraway Friends (1971) shows a tiny silhouette of the artist standing in the distance, at the edge of the sea and watching a magnificent sunset. The composition, placement and proportions are reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Monk by the Sea (1808–1810). In the work The Artist as Consumer of Extreme Comfort (1968) the artist is comfortably seated in a chair, his chin resting on his hand, looking at the fire burning in the fireplace, and above it hangs a photo of a ship in the middle of the sea. There is a dog sprawled on the floor at his feet. There is a faint light emitted by the floor lamp in the room. The photograph is black and white, and it is an undisputed interpretation of the famous etching by Albrecht Dürer Melancholia I (1514) which has similar motives. A brooding angel, head resting in his hand, looking at the sea in the distance, and a number of scientific instruments, not needed by anyone, are scattered at his feet. Just like in Bas Jan Ader’s photograph, in the etching there is a dog – a symbol of melancholy – sprawled at the feet of the angel. During the Renaissance, melancholy was considered to be an ailment which contemplative intellectuals were especially prone to. From the four types of temperament known since the time of the ancient world – sanguine, choleric, melancholic and phlegmatic – melancholic in particular was considered to be the most complex type which one had to live with and pay a high price for having that temperament type, similar to Dürer’s angel, at times not being able to partake in rational or intellectual activities when insurmountable sadness took over. In the majority of his works Bas Jan Ader is both author and participant. He places himself on the stage as a heroic figure, reminiscent of the artist-persona cultivated in Romanticism who was at the same time considered a genius and an impudent dandy. In his most popular work I’m Too Sad To Tell You (1971) we see the face of the artist in the foreground, incessantly shedding tears. As is evident in the title, the artist is too sad to divulge why he is weeping so bitterly, and truthfully, saying it would not change anything – the tears speak for themselves: a naked and direct expression of feelings. This video work has spawned a wave of imitations up until the present day, creating a sort of Werther effect of the late 20th century. There have been numerous remakes – video, cartoons and photographs. On Bas Jan Ader’s website (basjanader.com) there are several samples: Giancarlo Norese’s Starting With S, (2006), Megan Daalder’s I’m Too Tired To Tell You (2007), in addition the video-sharing website vimeo has Paul Baughmann’s animated film I’m Too Sad To Tell You. The phrases that Bas Jan Ader writes on the walls of his installations are also emotionally charged. Please Don’t Leave Me (1969), which is illuminated by a light bulb hung at the top of a ladder, reminds us of Jacques Brel’s Ne me quitte pas (1969). The heart-tearing cry splashed across the wall in big letters expresses one of the universal fears that we are familiar with since earliest child-hood: the fear of abandonment which, according to Freud, begins at the moment of birth when the child experiences the trauma of being separated from its mother. This fear is like a punch in the face and it conjures up unsuspected fears of emptiness, of abandonment, or it brings back terrifying feelings in anyone who has actually experienced abandonment. Thoughts Unsaid, Then Forgotten reminds us of how difficult it is at times to find the right words, how much we suffer until we are able to utter those words. How many times our message reaches our loved one only in our thoughts, how many letters we mull over but never put down on paper and never mail them! The installationperformance made in 1973 consists of the words written on the wall in oil and pastel Thoughts Unsaid, Then Forgotten, illuminated by a lamp attached to a tripod, and on the floor there is a vase with wilted flowers. The state of withering in a way symbolizes the process of forgetting, how the unsaid thoughts vanish, go up in smoke and merge with the background. Despite the “grammar” of the conceptual idea present in this installation, it also directly quotes from historic Romanticism, for example, the painting by Francesco Hayez Melancholy (1841), where half-wilted flowers emphasize the infinite sadness of a young woman, also evident in her gaze fixed into the emptiness. The unsaid thoughts chime with the theme of oblivion, but the object of the thoughts remains oblivious to them. Only the dying flowers testify to unfulfilled intentions; they are like footprints left by a virtual gesture that has never taken form. Each unsaid thought is destined to die, and the wilted flowers are reminiscent of the decaying fruit in 17th century still lifes and also speak of vanitas, the transience of things and our own mortality. The burden of failures and the tangle of our emotional world is heavy, but in the end we will have no choice but to take our unsaid thoughts with us to the grave. | |

Bas Jan Ader. On the Road To a New Neo-Plasticism, Westkapelle, Holland Digitalprint. 30x30 cm. 1971 Publicity photo Courtesy of the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam | |

| I do not think it is a coincidence that the first retrospective of Bas Jan Ader’s work caused such an uproar and ecstatic reviews. The works were presented at the branch of the Bologna Museum of Modern Art in Villa delle Rose during the opening days of the Arte Fiera festival. Giancarlo Norese comments, next to the acknowledgment, that Bas Jan Ader’s and his own works speak the same language, were always short and to the point: “the aesthetics of failure”. As we will later see, failure is like a red thread, a leading motif that goes through all of Ader’s life. The young artist is especially attracted by the possibility of experiencing failure, he mused over all the possible scenarios of failure, as well as the use of the word and its meaning in different languages. In English the word is phonemically similar to the verb ‘to fall’ and it makes him research the principle of falling in various situations. By the way, Ader is intrigued by the introductory sentence of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, which in German is as follows: “Die Welt ist alles, was der Fall ist”( 2). It is generally translated into English as “The world is everything that is the case”, however, the German verb ‘fallen’ is the direct translation of the English verb ‘to fall’, which in this case connects the world to things that ‘fall’ into it, happen by chance and might be described by the means of the languages. These things that fall to us also connect the world with its physical existence as such and emphasize the accidental nature of all existence. One more example of how Bas Jan Ader liked to play with words was the fact that he showed up at his wedding on crutches, because he had “fallen in love” literally. At Amsterdam’s Art & Project Gallery and Bremerhaven’s Kabinett für aktuelle Kunst he had a public reading of a dramatic story from a popular Reader’s Digest book, The Boy who Fell Over Niagara Falls(3), from time to time pausing to take a sip of water from a glass. The story plays with one of the many meanings of the verb “to fall”, here also forming part of the word “waterfall”, and speaks of the tragedy when the boy falls into it. The reading finishes with the last sip of water from the glass. In the film Nightfall (1971), the night falls when the artist breaks two lamps placed on the ground by throwing a concrete block on top of them… Bas Jan Ader’s research of the process of failure is not limited to individual destinies only, but they are the basis for a range of works which serve as a reaction to his compatriot Piet Mondrian, making references to the project of modernity in general – as we know, De Stijl(4) considers the artist to be a typical representative of Modernism. Four of Bas Jan Ader’s works created in 1971 were made at the famous lighthouse in Westkapelle, the same one that Mondrian painted several times between 1910 and 1920 until he found a geometrical solution where there were no more diagonals or colour nuances, and all that remained was black and the primary colours (red, blue and yellow). According to purists of the Neo-Plasticism movement, all the other colours and lines were redundant. The first photograph in the diptych Untitled (Westkapelle, The Netherlands) shows Ader wearing a hood over his face, all dressed in black: he is standing in the first photograph, but in the second one he has fallen down and lies at a ninety degree angle to his position in the first photograph. Both positions are references to Mondrian’s black vertical and horizontal lines. The hood over his head reminds us of two events: firstly, the fact that the Nazis shot Bas Jan Ader’s father, a pastor, when the future artist was only two years old; secondly, Renè Magritte’s painting Les Amants, which the artist created in the memory of his mother who drowned herself and was found with a cloth wrapped around her face. | |

Bas Jan Ader. Untitled (Weskapelle, The Netherlands). Digitalprint. 40.6x40.6 cm. 1971, 2003 Publicity photos Courtesy of the Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Bas Jan Ader Estate, Mary Sue Ader Andersen and Patric Painter Edition | |

| The other three works created in Westkapelle also use the same landscape: a path with bushes on both sides of it. The colour photograph with its symbolic name On the Road To a New Neo-Plasticism, Westkapelle, Holland shows the artist lying on the ground; his left hand is stretched out horizontally, the left leg is straight, and the right leg is bent at a ninety degree angle. Every next image has another object added to the composition, using the same primary colours approved by the De Stijl artists: a blue blanket, a yellow gasoline can and an emergency triangle in a red box. Evidently we are on the road to a new human interpretation of Neo-Plasticism. The artist’s black-clad body depicts the black horizontal and vertical lines, but the colour objects remind us of the famous colour squares of the “father of rationalism”. In the second work, Pitfall On The Way To a New Neo-Plasticism, Westkapelle, Holland which was created in the exact same place, we see the artist fallen to the ground and holding the same objects that we have seen in the previous work. I have wondered whether the word ‘pitfall’ might also be an oblique reference to ‘Piet-fall’, the fall of Piet Mondrian. The last work in this series is named Broken Fall (Geometric), Westkapelle, Holland and it exists both as a photograph and in the form of a black-and-white video. In this work, the artist’s body is stretched and rigid, and it falls to the side onto a blue trestle. The body which is in a vertical position skews more and more until it reaches a diagonal position (the diagonal rejected by Mondrian) and falls down flat on the earth: a horizontal position. In the photo version we see the artist’s body in a diagonal position which is unstable and inevitably turns into an unstoppable fall, because it is impossible to stay like that for a long time… In 1974 Bas Jan Ader created a sequence of important works which give a slight impression of irony directed at the Dutch master. There are eight sheets of paper coloured in red, yellow, blue and black, and a sketch for an installation with neon lights (implemented after the death of the artist) inspired by the words said by Dali: PIET NIET (“No to Piet”), who hated Mondrian’s strictly geometrical principles. The work Untitled (Flowerwork) is a series of seven photographs, and here we see the artist turning to flowers again. The artist takes apart and reorganizes a mixed flower arrangement until he ends up with three bouquets of flowers in blue, red and yellow – the primary colours of Neo-Plasticism. However, the works which Bas Jan Ader is famous for and which best express the concepts of failure and fall, the core motivating factors for the artist – a conceptual romantic – are the performances with staged falls. It is almost superfluous to point out the concept of the fall of Adam and Eve in Paradise, or the fallen angels. In these works Bas Jan Ader refers not only to the existential dimension, but to the artist’s calling in general – it is much easier to fall in this metier, to fall out of circulation, to descend into decadence than to gain success and make a decent living with the fruit of one’s work. There is no need to overemphasize the well-known truth that only a small proportion of artists are able to survive without additional employment, for example, as teachers, graphic artists or in other in supplementary jobs. In his work Broken Fall, (Organic), Amsterdamse Bos, Holland (1971) Bas Jan Ader is hanging by a tree branch over a stream. In the black-and-white video we see him unable to hold onto the branch and fall into the water. In the work Fall I, Los Angeles the artist is seated on a chair on a rooftop and then slowly topples off the roof, complete with chair. In the video Fall II, Amsterdam (both works were made in 1970) we see him approaching a canal on his bicycle. He is holding flowers in his hands, so is unable to hold onto the handlebars and “goes over the edge” into the canal… The theme of falling, however, goes beyond the comicality of farce and is not just a metaphor of failure or defeat. In Ader’s case there is always something metaphysical in a fall, it is almost like falling into a space where the laws of gravity have been cancelled, where the human being glides over the water or in wide open spaces, ends up in a world of nightmares, and after all it is also a fear of the end. Bas Jan Ader’s art was indeed influenced by reflections on death. The main work to be mentioned in this regard is the series of two colour photographs Untitled (Swedish Fall),1971, which is a sublimation in art of the artist’s childhood trauma, namely, his father being shot by the Nazis. In this series we see a forest, and in the background between two great pines there is a black-clad figure (Ader). In the second photograph, taken from the exact same spot and with the exact same composition, we see that the distant figure has fallen to the ground. Giancarlo Norese has said: “Bas Jan Ader’s art can be defined only as sacred art. If the word “religion” were a positive word, I would use it.” There is quite an abundance of references to religion in Ader’s creative work. His father was a pastor, and the artist one day decided to go to Jerusalem by bicycle. This destination was dramatically overshadowed in 2008 by the journey-performance of the Italian artist Pippa Bacca, a cousin of Piero Manzoni, who, dressed in a wedding dress, tried to hitchhike to Jerusalem but didn’t get there…(5) Pippa was thirty-three years old – as was Jesus when he died on the Cross and Bas Jan Ader when he took off on his final voyage. The artist was not only seeking to set a new world record by single-handedly sailing across the ocean in the smallest boat ever, the Ocean Wave (length of boat – four metres), but he was searching for something bigger. He was searching for lost time, the absolute, the infinite. Himself and the sea. Himself and the almighty ocean. Bas Jan Ader set sail from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, on 9 July, 1975 in order to finish his triptych In Search of The Miraculous. The first part of the triptych One Night in Los Angeles is a series of eighteen black-and-white photographs, where Ader is seen crossing Los Angeles at night so that he would reach the coast of the ocean by dawn. Scribbled in hand at the bottom of each photograph is a line from the Coasters song Searchin’. Before he set off, a choir performed sea shanties and the walls of the Los Angeles gallery were adorned with the words: A life on the ocean wave. Ader took with him on board the boat Hegel’s ‘Phenomenology of Spirit’, in which the spirit finds itself when it has dialectically travelled through the whole of nature, where the inadvertent rules … Greetings from beautiful Ader Falls; All is Falling; Rolling into a freshly dug grave; I can think around the corners; Whole series of photographs on dead in ocean, being washed ashore; My body practicing having been drowned; The sea, the land, the artist has with great sadness known they too will be no more.(6) (From Bas Jan Ader’s notes.) Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča (1) Happiness (Spanish). (2) The translation offered by the author with the verb ‘to fall’ is closer to the metaphor of falling, and in colloquial language it may also mean: “to happen by chance”. (3) An ambiguous title, where ‘to fall over’ can mean both ‘to fall over the edge’ or ‘to fall in love’. (4) De Stijl (literally ‘The Style’ in Dutch) – a Dutch artists’ movement named after the magazine founded in Leiden in 1917. The key representatives of De Stijl were Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian, Vilmos Huszár, Bart van der Leck, Gerrit Rietveld and others. After Theo van Doesburg’s death in 1931 the activities of the movement dwindled, but its influence continued, especially in architecture. (5) She was raped and killed on 31 March, 2008 in Gebze, Turkey. (6) Bas Jan Ader. “Please don’t leave me”. Catalogo Mambo, Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, was published by Comune di Bologna), page 21: a note from Ader’s notebook which was mentioned by Brad Spence in the exhibition catalogue, which was open to public from 25 February to 20 March of 1999 at the Art Gallery, University of California, Irvine. | |

| go back | |