|

|

| “I wanted the curtain to open and for Lenin to be on the stage” Margarita Zieda, Theatre Critic | |

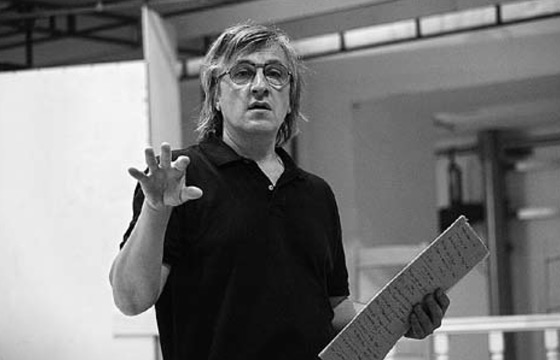

| At the beginning of December in Berlin, having watched four per formances representing very diverse aesthetic directions at the RusImport theatre festival held by the Berliner Festspiele (the per formances ranged from the politically critical Citizen Poet project from Moscow to St. Petersburg’s AKHE Engineering Theatre mobile installations), I was left with the feeling that there’s something that we don’t know about Russian theatre today, even though works of theatre travel from Russia to Rīga all the time. Judging from posters around the city, there’s almost a nonstop stream. Dmitry Krymov and his creative laboratory, however, have never been experienced in Latvia. Not within the framework of selected winners of Russia’s national Golden Mask Award, nor in the Homo Novus or Homo Alibi festivals organised by the New Theatre Institute. Meanwhile, Krymovs’ works travel the world. The legendary critic Michael Billington, who writes for the British newspaper The Guardian, urges his readers not to miss the chance of seeing Krymov’s interpretation of Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream (As You Like It) at this summer’s huge international Shake speare festival: “This is not your standard Shakespeare but a hilarious piece of controlled anarchy.” First performed in StratforduponAvon, the city where Shakespeare was born, Krymov’s latest performance went on to one of the most highly regarded European festivals – the Edinburgh International Festival, where it received the Grand Prix in 2012. This theatre has not gone unnoticed by world avantgarde the atre icon Robert Wilson, who invited Dmitry Krymov to come to his Watermill Centre creative laboratory in New York and to share his experience. The genius of dance Mikhail Baryshnikov, in turn, who also lives in New York, invited Krymov to compose a new stage work for him. The production In Paris made the transatlantic transfer from New York to Europe, but wasn’t shown in Russia, however. Since his emigration, Baryshnikov has never once performed there. It’s complicated. But Dmitry Krymov’s home is in Moscow, at the School of Dra matic Arts. The theatre with two halls was built by the City of Moscow for its outstanding director, Anatoly Vasiliev. Very soon afterwards, though, there were complaints that the theatre was not present ing performances every single night and wasn’t jampacked with audiences. Vasiliev has always believed that it takes time to reveal something, and even if his explorations have taken months or years, they shouldn’t necessarily be always shown to the public. The com mercial theatre demands imposed on him offended Vasiliev, and he left Russia. Although many times he was invited to come back, it was over a decade before he finally returned to Moscow. Anatoly Vasiliev was the one who noticed Dmitry Krymov’s first performances, created together with his students from the Sceno graphy Department of the Russian Academy of Theatre Arts (the former GITIS), and invited them to come and work with him at the School of Dramatic Arts. This gave them the opportunity to develop a performance for as long as the work required it, in this way providing an opportunity for them to search as well as to find their own paths in theatre, paths which couldn’t be confused with any other. The the atre aesthetic created by Krymov is quite distinctive. Even though it incorporates inventions from the whole world’s theatre, Krymov has been able to create his own world, one that differs from all oth ers. It began to develop at the beginning of the new, 21st century together with student stage designers as a system of visual images, a poetic theatre to be comprehended visually. Later they were joined by students from the acting course, enriching this incredibly strange Krymov world with words. Even though Dmitry Krymov has become famous as a director only in the last decade, he is a person with considerable life and art experience. Born in 1954, he was working in theatre already from the mid1970s, creating stage designs for more than 100 performances. Krymov’s laboratories, which can be found on the internet on the www.krymov.org home page, begin with the portraits of his parents. They are Anatoly Efros, one of the most important and at the same time most refined 20th century Russian directors, in essence one of very few continuators of Stanislavsky’s work, and Natalya Krymova, one of the most significant theatre critics in the former Soviet Union. Already from early childhood Dmitry Krymov was exposed to a re fined and deep understanding of the nature and essence of theatre, just as he came into contact with Soviet ideology (rejected his par ents) which had created the new barbarian – the Soviet person. This is also echoed in Krymov’s theatre – universal artistic explorations are interspersed with reflections about the history of his country and the general quality of life today. | |

Dmitry Krymov. 2012 Photo: Natalia Cheban. Publicity photos Courtesy of the Dmitry Krymov Laboratory | |

| One of his most famous works Demon. A View Above, for which Krymov as Best Director received the Russian theatre awards Crys tal Turandot and Golden Mask, aimed at changing the viewing per spective, and as a consequence, the thinking perspective as well. By seating the audience up high, on three levels of the circular the atre – and creating the performance in a little area at the very bot tom, Krymov not only allowed the public to view things and process es from a bird’s eye viewpoint, but also began to vary the viewpoints by changes in images, changing and diversifying them to the extent that the audience’s consciousness would finally catapult into space and the view would reach the perspective of the Universe. In one of the latest works, Gorki 10, which was also brought to Berlin, Krymov has turned his attention to the seemingly exotic pages of theatre history which are no longer leafed through – all those countless plays and productions about Lenin, revolution, war, the emergence of the Soviet person, which didn’t leave theatre stages in the Soviet Union, including Latvia, right up until the collapse of the USSR at the end of the 1980s. The Gorki mentioned in the title is the place where Lenin convalesced after an assassination attempt on him. According to the artistic fantasy of Soviet playwright Nikolai Pogodin, Lenin rang his female employees at the Kremlin from Gorki one day and said that he’d be arriving. In order to think. Krymov had multiplied this delirious situation by ten in his production, showing the scene in the Kremlin office in tenfold exaggeration. And, also in order to think, along with Alexander Pushkin’s Boris Godunov, Kry mov selected a number of Soviet plays which contributed themes to the production. Nikolai Pogodin’s The Chimes of the Kremlin, the central theme of which, according to the author of the play, was Lenin and the intelligentsia; Anatoly Vasiliev’s war story ‘But the Dawns Here are Quiet’ about female soldiers, all of whom became cannon fodder and were later mourned by their officers, and used these themes to develop his production. It also included a scene from Vsevolod Vishnevsky’s Optimistic Tragedy, in which a woman, having boarded a ship, complains that a sailor has stolen her purse. The sailor is punished – a sack is placed over his head and he is thrown into the sea. Krymov concludes his production with this scene, includ ing in it a woman of contemporary appearance, with smudged make up and a heavy dose of alcohol in her body and mind. In the hunt for the thief of the purse, one person after another on stage gets shot until, walking over the corpses, the woman finds the purse and she happily goes on her way. Into presentday life. The Soviet personmonster in Dmitry Krymov’s performance is revealed in a world of absurd humour. But the extremely funny processes taking place in it, which make one laugh out loud uncon trollably (a number of acquaintances who were watching the perfor mance in Berlin even encountered problems with emigrants from Russia who were sitting alongside them, and who reproached them saying that it interfered with their enjoyment of the performance), at one instant become terrifying, although everything on stage is taking place exceedingly pleasantly. Lenin – a little man – is sitting by his green lamp and is conversing in a child’s voice with the engineer Za belyn, who, having been recalled to the Kremlin, has brought along a set of clothes to take with him to Siberia. Next to him stands an “iron Dzerzhinsky”, which suddenly transforms into a centaur. And every so often Krupskaya walks into the office with a cat. This conversation with Dmitry Krymov took place while on tour in Berlin. Outside the window there was snow and sun. Dmitry Krymov: So, what would I like to find in this labora tory? Margarita Zieda: Or at least – what are you looking for? What sort of issues are you working with? D.K.: (Laughing) Well, I’d like to find the thing that I’m looking for. I don’t know, I think that overall theatre is boring. I don’t want to be boring. And to be powerful in this nonboringness. Emotional. Terrible. To touch upon very cardinal themes of life. When you brush with those sorts of themes, the terrible comes out, whether you want it to or not. Recently I read the answer that the wonderful philoso pher Meraba Mamardashvili gave to the question of what is philoso phy: “It is the freedom to think about any question from the perspec tive of the final point.” I think this is good and can also be related to what we’re searching for. I am interested in researching today’s theatre language, and trying not to do the same boring things which were in it yesterday. Not just ‘not repeating’ what others have done previously, but also what we ourselves have done. Although it’s hard to change your own fingerprints. M.Z.: What bores you in theatre? D.K.: It’s the same all over the world. Explicitness is boring. Usually, what will follow already becomes clear to me in the first second, and very rarely does anyone overturn this feeling, smash to smith ereens what I’m expecting. Maybe I’ve got it wrong, but I think that the person of yesterday and the day before that was completely dif ferent. And each succeeding minute doesn’t have to be similar to the last. But that’s pretty hard to achieve, as you have to put yourself in the place of the person sitting in the audience, get under their skin, and understand that you’d get bored by something you’d devised yourself. And it usually happens extraordinarily quickly, if you’re capable of being critical of what you’ve created yourself. Well, see, that’s the foundation. But languages can be very diverse. They can even be tedious – boring – a person talks and talks, and talks, it can be like that too, nothing is forbidden. And still, every minute I as the audience have to move forward. I’m not convinced that it’s possible to do this with the help of text only, as it used to be, with some kind of storyline. To my mind, theatre has huge resources, so it should be possible to move forward by various means, not just through the story, though the story, too, is a component. It’s the emotions that are important. And not all of the ideas have to be understandable. My joy is inventing language. And without excessive modesty I have to say that we have already come up with it. But the lines of a poem can be diverse, they can be written in hexameters, but they can also be written in iambic verse. M.Z.: What forms this language? D.K.: The images. The clearer they are and simultaneously more mysterious, the better. The more they draw you in, the better. It’s a sort of image journey. Metamorphosis. I could name all of my perfor mances like this: Metamorphosis 1, Metamorphosis 2, Metamorpho- sis 3, Metamorphosis 4... It is the transformation of one image into another. You could even take a plastic glass and create experiences for this glass, in which you could recognize Hamlet and everything else that is possible. This plastic glass melts into a woman’s hair clasp, and then into ice. And for all of this you can find substantive dramatic arguments. M.Z.: But how do your performances develop? What is there at the very beginning? In your theatre you don’t usually take a complete play for interpretation. D.K.: It’s different each time. Speaking of the Gorki 10 perfor mance, for example, I wanted the curtain to open and for Lenin to be on the stage. I don’t know why. Not on Lenin’s behalf, nor also against Lenin. I wanted to understand what could happen in this peaceful painting if you were to take a really good look into it. M.Z.: What is this peaceful painting from which this work of theatre has evolved? D.K.: It’s a very well known chrestomathic painting called Lenin in Smolny which hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery. In my childhood, whenever we went to this gallery we thought that, while the little old lady wasn’t watching, we had to touch the painting. Because we felt that the furniture coverings in that painting were dusty. It had been painted that way, by Isaak Brodsky, a Soviet painter. I was interested in finding out what would happen if you really looked into this paint ing. How does it come to life? What is Lenin reading? What will hap pen next? Of course, there’s a goodly dose of Daniil Kharms’ absurd humour playing a part in this looking process. Because the time of that realistic horror has passed. The horror has increased. Horror is Guernica, but that work also Picasso painted after the war. And after Picasso you don’t know how to portray horror any more. What is to follow? Because language continues to develop, all the time. Noth ing stands still. Horror – perhaps. But the language which describes this horror is developing somewhere. And everyone develops this language in accordance with their own fingerprints. Well, we want to have a laugh, but about this horror. However, laughter about horror isn’t simple laughter. It’s laughter about horror. M.Z.: In theatre there’s a fairly enduring view that people ex- press themselves directly through language. In your theatre, the level of visual expression is more powerful than the word. D.K.: But how about those who are mute? How do they express themselves? They can’t speak. We too are mute. At first, when artists began to develop our theatre, they were also mute, as they couldn’t speak. If they did, it sounded quite disagreeable on the stage. But they knew how to do a lot of other things and expressed themselves in a different way. Then actors appeared who could speak. And a new connection was formed. We’re sort of partly mute – we can say some thing in words, but there’s a dog sitting next to us. M.Z.: In your production there was a cat which was being carried around by Lenin’s wife Nadezhda Krupskaya. Until at one moment she took the cat by the tail and threw it out the Kremlin window. The cat was alive, then dead, then alive again. D.K.: Yes, and at other times that dog which sits next to us runs after the cat, and overall it’s no longer clear what’s happening. M.Z.: Your theatre website on the internet is headed with portraits of your parents – hugely important personalities in the USSR in their time. How have they influenced your understand- ing of the theatre? D.K.: They are me. With every movement that I do in the theatre, whether I like it or not, I think about what they would say. And I don’t know the answer. It’s quite a strange feeling. My father once told my mother: “You know, if I can’t find any point beyond this scene, the overall sense...” And then it’s not interesting for me either. I cannot develop a scene as a scene, until and unless I find some abstract, eternal truth to the scene. It’s what I was telling you about the char acterization of philosophy. Mamardashvili said that you can theorize about anything, only it has to be done from the perspective of the final point. And this is very similar to what I try to do in the theatre. I think that my father would have liked this expression. It’s a wonderful thing. His works could be researched from this perspective, or even mine. I’d like to hope so. Sometimes it seems that it’s all a commo tion, but I like it if this commotion has something of the image of an eternal commotion or eternal movement. But it could well look like some school’s amateur theatre, or the ‘Diligent Hands’ handicraft group, or the ‘Arteks’ pioneer camp. The sillier it looks, the better. But the one who is able see something behind all this will be unex pectedly touched. | |

Gorki 10. Scene from the performance. 2012 Photo: Natalia Cheban. Publicity photos Courtesy of the Dmitry Krymov Laboratory | |

| M.Z.: Your latest work is called As You Like It after the Shakespeare play... D.K.: After the Russian provincial author Shakespeare’s play A Midsummer Night’s Dream. M.Z.: But in your biography, your work with Shakespeare already began with the creation of the stage design for Othello in Anatoly Efros’s production. Has the universe of visual images which we see in your laboratory changed through developing your own theatre? D.K.: Let’s not exaggerate. At the time when I created for my fa ther the stage design for Shakespeare’s tragedy, I didn’t understand anything. I could only tell you what was on the stage. Two gothic seats on which people sat. It was all a bit reminiscent of the works of Alexander Tischler. They opened and closed in a sort of crescent – like the shell of a nut – and squashed something like a camp bed, which also stood there. M.Z.: Did Shakespeare's country of birth, for which your latest work was created, somehow influence the world of images which otherwise is so very strongly influenced by Russia? D.K.: Well, you know, there’s this great simile in the Bible. Jesus Christ has sat down to eat supper at some place, and the owner re bukes him for not washing his hands before eating. To which Christ replies – it’s not important what goes into your mouth, but rather what comes out of it. M.Z.: And what came out of your mouth for your laboratory in England? D.K.: Jokes. The performance was about how people create a per formance. We took only one scene from A Midsummer Night’s Dream – how craftsmen create a performance. M.Z.: Night. Hay. The Moon. D.K.: Yes, yes, that silly scene that everyone laughs about. Having experienced so much throughout the course of the play, here people can оттянутся (relax, have fun – Ed.) with fools. Some clowns came and performed something. And I decided to look into this clowning. In general, one can see there the genealogy of love stories. They’re like the first love stories, in very archaic form, from when plays had not yet been invented. The two first people fell in love with each oth er, and some clumsy people told the tale. M.Z.: In Shakespeare’s time the stage was quite empty. Almost everything took place in the mind of the audience. D.K.: It’s a question of language. That world, when someone on stage walked around with a sign saying “the sea” and the viewers imagined the sea, is finished. That’s no longer surprising. You have to surprise. Language is there for you to say “the sea” and the viewer will sense the sea. Two characters were important to us – he and she. (During the performance these characters, Priam and Tisbe, from being children become old people. They are huge dolls whose faces, like in Fayum portraits of the dead where the painted faces change, become adult and age – M. Z.). And fifteen people who are trying to tell us something. The actor and the role. The actor and the play. The canvas and the artist. Creative activity and the artist. How you tell it. How you worry that you won’t be understood. Last night a small girl came up to me after the performance and said that she hadn’t understood my show. And immediately I found myself in the role of that craftsman whose performance also wasn’t understood. That’s what my pro duction is actually about. That people don’t understand it. They don’t understand half the performance. In the end I came up with the kind of, I’ll truthfully say, fairytale that they understood. In a word, pretending to be a fool. But perhaps also being one in reality. Only behind all this there definitely has to be something. But then again – the sillier the better. Well, for example, the portrayal of Lenin. What could be sillier? And, if you didn’t understand, we’ll repeat it again, and if you still didn’t understand, we’ll repeat it yet again, but, if you still didn’t understand, we’ll call out Boris Godunov for you in a moment and he with Pushkin’s text will explain to you how Russian life is set up. I think that you have to make an effort, and the trouble is cer tainly worth it, if you truly try. Hamlet, if you’ll excuse me, also didn’t achieve justice. He simply wasn’t patient. He tried, but it got him no where. He killed a lot of people but didn’t achieve justice. But these efforts themselves went down in history. M.Z.: To understand better the path of transformation of these images, tell us about the In Paris production which you cre- ated with Mikhail Baryshnikov. What is the image in this show which keeps continually transforming into new versions? D.K.: It’s loneliness. I felt that I was on the right track when I un derstood that the performance should already begin while the public is entering the hall, and Baryshnikov, although everybody knows him and they’re coming to see him, is standing in the middle of the stage, talking about his life, but very quietly. And everybody feels somehow uncomfortable that they have come in and a person is standing there and talking about something. It’s as if you should find your seat and go and sit down, unavoidably making some noise, but it’s sort of un comfortable to do that because there’s such a famous person there already, talking about something. And for this to go on for a long time. To put the audience, to put everybody in such a very uncomfortable situation, that... He is talking about loneliness to a public who is just arriving from the cloakroom where they’ve left their coats. See, this is the first image which transforms into the next and then the next and so on. A person is standing on the stage in the dark and talking about loneliness, but nobody can really hear him, only a few individual words are audible. But these don’t link up into a coherent story. And suddenly it really begins. We came up with the idea of the text crawl ing about the whole stage, starting with the forestage, and heading into the depths. They are letters, the huge letters of this monologue. It’s as if you’re nothing. And you’re the nothing of the world. You are as lonely as Gogol’s Akaky Akakievich, whom nobody needs. An emigrant, who’s lost his homeland, his army, his love. But with some sort of willpower, whether Bunin’s (Ivan Bunin Russian writter – Ed.) or our own, it is brought up to the level of the world’s loneliness. This tiny loneliness and the world’s loneliness. In the story, this scene is described very quickly – how he enters the cafeteria and notices a woman sitting at a table, the woman he loves. We devised a scene that lasts for quite a while on stage, about seven minutes. He comes in and hangs up his hat and coat, but they fall to the ground. He can not hang up neither his hat nor his coat. And it looks like mockery. By about the fifth time around you understand that it is mockery. But you can’t understand who is making fun of him. Most likely it is destiny, and how this person’s battle with a nail ensues. His hat and coat won’t stay on the wall. To me it seemed like the image of a loser, only the loser had once been a general. His selflove is running very strongly, while unable to hang up this coat. In Russia it could be hung up, but in France the coat won’t stay. And that’s it. The goal is how to transform one image into another, and to develop a story from these images. That’s why it differs from the primary source which we took as the basis, because we are not telling this story, but rather explaining a theme. It’s not important when they met and where they went from there, the themes are the important thing. Loneliness, the rendezvous, the walk, the place they entered. Not when they entered, but where. What is it? They went in before going home. Then headed home. How he suddenly, unexpectedly died. What is it? Like a series of visions. M.Z.: Did you take away dance from Mikhail Baryshnikov in your theatrical story? D.K.: In the end he does dance, but the dance, too, is like an im age. For me, it is not simply dancing. And for him, among other things, as well. It’s like the image of a battle, like a corrida. The last corrida. With destiny. With loneliness. He is dancing with his general’s great coat. It’s a White Guard greatcoat. And he is like a matador who is killed by the bull. But the bull cannot be seen. It is the ambience of emigration. Or perhaps that of destiny. Paris’s. M.Z.: Your universe of shows is made up of not only visual, but also sound images. D.K.: There was live music, there was drumming, accompany ing him on his final journey. It’s the funeral of a general. And there is one more image in this show: the choir. All of the images, the woman, the waiter, all of the people sing about what he is doing. He is doing something and they sing. At times they sing about what he is about to do. He hasn’t even died yet, but they’re already chanting over him the otpevanye (sung hymns and prayers over the departed in the Orthodox religion – Ed.). It is the otpevanye for a person who is still alive. The end is already known – in two days he will die. And the otpevanye has already started. But in these final two days he has managed to fall in love, gone to meet her, taken the woman to the cinema, spent the night with her and died. And they begin the otpevanye at the beginning of the second day, and continue right through to the end. Because it’s a kind of doom, doomed to loneli ness. See, that’s what it is. M.Z.: Did the theme of loneliness arise from thinking about Baryshnikov? D.K.: First of all it bothers me. It doesn’t give any peace to Bunin either, or to Baryshnikov, or to all the other people as well. Perhaps it’s just that they don’t even suspect it yet. Translation into English: Uldis Brūns | |

| go back | |