|

|

| The body, the human condition and the dialogue with the viewer Laine Kristberga, Screen Media and Art Historian Gordon Sasaki | |

| Gordon Sasaki is an American visual artist living and working in New York City. He has been working as a Community and Access Educator at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for 10 years now. Sasaki’s work focuses on understanding aspects of the human condition through the universal form of the body. He is interested in the symbolism of the body as a vehicle and container of meaning – remarkable in its complexity and still quite mysterious in its understanding. Due to an automobile accident, Sasaki uses a wheelchair and being an individual with a disability, the artist is committed towards art and education that stems from a personal understanding of art transcending boundaries and creating opportunities for dialogue. Sasaki’s exhibition Surface Tension was on view at the Art Academy of Latvia from 18 October till 6 November, 2013. The exhibition was also supplemented with a public lecture and a workshop. We met for an interview at the International Department of the Art Academy and refer to the exhibition as “the show upstairs”. Laine Kristberga: Now you are working in the Community and Access Department at MoMA, but maybe we could start with the story of what happened before that? Gordon Sasaki: I think it’s totally relevant and that’s where I would naturally begin. My work is very personal. It is some kind of a self-portrait, but in many ways I try to incorporate it in connection with larger society. Because to me borders are, in many ways, problematic. Even in the process of sewing. I don’t know how to sew at all. Just the process itself is very interesting, as it is generally associated with women’s work and yet I feel like it’s something that I want to explore. The thing that brought me to it was that I had an automobile accident and surgery after that. And on my back I have a long scar which was initially sown with a needle and thread. When I looked at it in the mirror, it conjured up images to me. This is where sewing began. Intentionally put together in kind of haphazard way like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. By making these composite things that are might be disquieting or even uncomfortable for the viewer, but to me are very real, I speak not only about myself, but about the human condition. | |

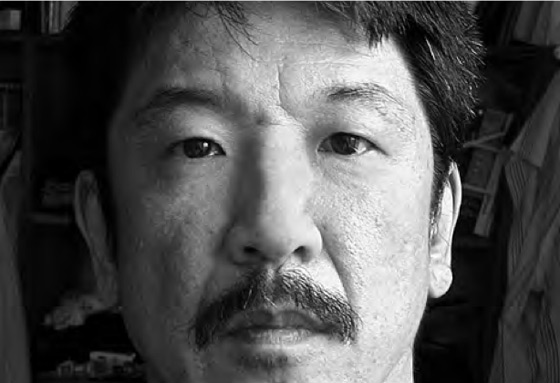

Gordon Sasaki. 2013 Photo from the private archive of Gordon Sasaki | |

| Initially it was in 1982, when I was still in college studying art. I mean, I always knew I was going to be an artist. I could never do anything else. This was my vehicle of communication. As a child, I drew and painted a lot, that was the way I communicated with those around me. It was always natural. But after I had my accident, I was very sceptical about the things doctors were telling me. I asking all kinds of questions, because I wanted to understand why my legs are not working. Common sense questions, but at the time doctors were not used to being so open with patients about their practice. This was the beginning of my exploring the human body from a physiological perspective, this lead to other literature and philosophical explorations about the human body. I was interested in this idea of the body as a container, not only from a Western point of view, but also from an Eastern philosophy view. I explored the body as a kind of metaphor for the human condition. This is where my interest in working with the figure comes from, including the use of many different media, as you can see it upstairs. I also explore the use of materials... Like the black figures upstairs. They are made out of rubber inner tubes. With the clear plastic figures, I am exploring the idea of transparency and invisibility. Because one of the things about disability is that it tends to be very invisible, not only from an economical standpoint, but also from a political standpoint. Even with the light pieces, I am interested in the ephemeral and fleeting quality of light. Light has no form in itself, but it illuminates the forms that surround it. In all cultures throughout history, light has always had some kind of spiritual or metaphorical connection. I’m interested in presenting alternative perspectives. I like the idea of education being a form of communication. With an emphasis on sharing ideas as opposed to creating decorative art. The power of art lies in its ability to communicate across borders, languages and time. L.K.: What about other people – art critics and theoreticians – contextualizing your art? Do you find it conflicting or clashing with your ideas? In my experience, I have come across situations and artists who only prefer reviews or critique on their work to be written in a poetic, essayistic manner, so that it would add another semantic layer to the work. How do you feel about your works being contextualized? G.S.: I believe that people, when interacting with art, bring their own history. They can only see what they see from their perspective. And this is always a very subjective perspective. So, whether it is a causal viewer or an experienced artist, or an art critic, I don’t see it as one being more valid than the other. I think the ability to feel is all that I ask. I don’t think there is any singular interpretation of my work. I work very much in a very egocentric way. I don’t care what people think, or what they write about. It’s perfectly fine with me – positive or negative, or whatever. I really don’t care, because I’m doing the work for myself. Interpretations vary very tremendously. Often what people say or write about my work reflects their own perspective rather than mine. If it’s about communication, that’s great. I want to share the dialogue with the viewer, and want to know their histories and how the work brings up emotive or psychological states. I don’t want my work to be didactic or singular in its interpretation.. L.K.: What’s your working process? Do you have assistants? G.S.: I do all my work on my own. I work in parallel with many works simultaneously. I don’t work on one work and then finish it. I generally work on four or five works simultaneously, in different media: in 2D, 3D, photography. Even with video or whatever. L.K.: As regards your video works, in nearly all of them the dichotomy between movement and stillness is evident - both in terms of cinematography and disability. Also in terms of the perspective, because the videos are shot from your perspective sitting and moving around in a wheelchair. It reminded me Chantal Akerman’s film Jeanne Dielmann, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), where she purposely filmed the entire film from her perspective (she is short in height), so as to emphasise the woman‘s or woman director‘s point of view. G.S.: I created these video works in different cities and they are an of exploration travel and perspective, and how an alternative point of view can influence perception. I purposefully fix the frame so that the audio becomes equally informational, in the sense that I want to try to address what is outside of the frame of visual reference. My perspective is low, like that of a child‘s, but this is more as a matter-of-fact. In all of my work I try to maintain the integrity of the material, as I do with rubber inner-tubes or rice paper. L.K.: Also, the video you filmed on Christmas Eve brings up a lot of questions. Do you feel isolated and lonely, being a disabled artist, or solitude actually is the preferred state when making art – being undisturbed by the dynamics of the city, when even commuting takes so much energy and tolerance? G.S.: Is regards the anonymity of the city, one of its greatest fascinations is its ability to render the individual alone amongst the many, I think more ‘alone’ versus ‘lonely’. My compositions tend to be minimal because I find inspiration in a certain Japanese aesthetic, more meditative and introspective, and as with all searches within, that journey is alone. As is the journey between the viewer and the work of art. These video works are begun without an agenda and focus on process, they are spontaneous, and I never know what I might encounter. What I do know is that my path is not same as most... L.K.: Do you often work with your own body? G.S.: Yes, absolutely. I did not have the opportunity to bring some pieces to the show upstairs. One of my inspirations has been the work of female artists. What inspires me about some of the, I recognize the desire for quality. It’s about identity. And to me it trespasses any kind of gender specifically. The hierarchy and the politics of art, especially in New York, is very obvious . Reasons why one artist is promoted over the other may not necessarily be about the work. There may be many other things involved. I’m sure it’s the same everywhere, art is a political venture. L.K.: How would you define the art environment in New York? What is the path from being an art student to becoming a recognized artist? It must be very difficult in a city like New York. G.S.: In some ways, sure. The challenges I face are in some ways are even more difficult than other individuals do. Because there are galleries where I cannot physically get in. Like the school here – I have to be lifted up stairs. If there is nobody around who lifts me up, then I don’t go in. These are different mindsets. Because we have these paradigms when we think this is the way it is, because it has always been this way. My perspective is more about other possibilities and other perspectives that can or do exist. We just have to open our minds and think about different ways to approach situation. Whether it’s architectural or conceptual, it seems the same if we are talking about barriers. It’s about making that connection, about collaborative thinking, finding out ways that we can negotiate or collaborate together. | |

| |

| L.K.: You are originally from Hawaii. How do you feel about your identity now? Do you find yourself as an American, or do you feel a strong connection with your origins and roots? Does it play any role? G.S.: It does. I’m a fourth generation American. My great grandfather went to Hawaii in the 1860s. And because of the oppression of the Japanese culture during Second World War, a lot of cultural practices were repressed and actually illegal. So, for example, my Japanese language abilities are very limited. I went to Japan and I spent a year there to better understand its culture, and my own ancestry. In my travels, I’m always interested in trying things that are connected to the place, for example, the national food. L.K.: Would you reflect about identity issues in your works as well? G.S.: For example, the light pieces – the lanterns – upstairs are made of rice paper. I wanted to take the Japanese tradition of lanterns and bring it to contemporary art. Also, in terms of the compositions – they are very minimal. I like very simple, just almost object-background relationships, very minimal, so the hope the work becomes more contemplative, reflective and hopefully introspective. L.K.: Is space a crucial factor in exhibiting your works? Would you prefer a white cube gallery space over, let’s say, an abandoned factory? G.S.: It depends on the particular work, because context is so critical. Even when I think about my own identity – am I the same person in Latvia as I am in New York? I mean, I feel the same, but from an external perspective I’m different. Like, I was at the Design Museum the other day and the children were so fascinated by me. I felt they wanted to talk to me, but they were shy, as children can be, so I just smiled at them. But in New York this does not happen. So there is a difference in meaning, because of a shift in and context. And I welcome that kind of difference in whatever space the work is shown. My feeling is that the figures could just as well be thrown on the ground. How would they be taken in? Especially the clear figures, because I envision them to be almost like a snake climbing out of its skin and then being reborn again. And then its skin becomes a historical artefact. But of course, if I exhibited these works in an industrial space, it would again be very different. Or if they were placed on a surgical table, for example. L.K.: I remember from translating the titles of your works that there was one work where you used your own skin, but unfortunately it’s not in the show. G.S.: Yes, that was the work titled Self-Regenerating Pumps. Unfortunately, the shoes were too fragile to travel. In Hawaii I was on the beach too long and I got sunburnt. As a result, my skin started to peel off. I saved that skin and put in my thesaurus. And then, several years later, I thought I want to make these shoes. So I used copper wire, and a statically charged brush to get static electricity out of my hair. Then I formed the basic structure and built the shoes out of the pieces of my skin. The shoes themselves are quite small. My interests in using the “pump” shoe form is because it has so much meaning, culturally and individually. I have other works with body parts, too, like feet, hands, penises. But the problem with these works is that they are challenging to display. For example, I needed vitrines for the penis pieces. Because they are meant to hung on the wall, like coat hangers. Someday soon I’ll probably make brass replicas. Right now they are made of goldleaf, and hand-curved wood. But if they are made out of brass, people can actually hang their coats on them. L.K.: Could you tell a little bit more about your role and duties at the Educational Department of MoMA? G.S.: We have four different departments. I work specifically in the Community and Access Department, which basically services the underserved and disabled populations. Since my injury, I have been working and training specifically in this area, because it is based on a kind of a personal interest. But also, the work that is created by someone who is not an artist can be the most real work that exists. It’s beyond the intellectualized art. It’s very visceral and coming from one’s guts. 30 years ago it was not even recognized, but now it’s become more popular. That really is because of its commercial value. I’m interested in something that is very sincere as opposed to finely crafted. There is another beauty there and that’s why a lot of the work that I’m presenting here is about skin. It’s just surface. But we can get through that surface to something else. Like the black rubber figures upstairs – they have zippers. The title of the work is Gimps. Do you know this term? L.K.: Is it a fetish suit? G.S.: Sometimes it is associated with fetish. But it is also a term used to describe people with disabilities. L.K.: I didn't know that. G.S.: But it has that fetish connection, too. L.K.: We had many difficulties trying to translate the titles of your works in Latvian. On many occasions, we had to use the descriptive method, because it was impossible to define it in one word. G.S.: My idea is that any time you translate a language – even from culture to culture, but also from visual to written - something is changed. Something is substituted. Gimp is actually a slang term, it is derogatory and it has a negative connotation. There is this “disability culture“ movement that started about 20 years ago and it’s about self-determination within the disability community. Gimp used to be a negative term, but now it has been elevated to a kind of a friendly term. But we use it only among ourselves. By using the once-negative term on an everyday basis, its meaning is subverted and almost desaturates its power. This kind of perception seems very interesting to me. Because when I look at the general male position in art – to be reflective and to talk about the body is much more about the female artist’s position. If true, why is it so? L.K.: It must be a historical phenomenon. G.S.: Exactly. Even to create these images of wheelchairs. Like Mona Hatoum – she has done some pieces with wheelchairs, but very different from mine. Does it mean something different, because I use a wheelchair? What if somebody who does not use a wheelchair makes a painting of a wheelchair? Is its meaning somehow different? This kind of a connection between the artist and work is what interests me. If an artist is a celebrity, how does that inform the work? Particularly now, in contemporary society with mass media, specifically the internet, how does it influence identity? Are geographic or political borders relevant anymore? What are the relationships between individuals and the artwork? And how does it connect us or disconnect us? What also seems really interesting to me, is the dichotomy between the body that is ultimately personal and intimate, but simultaneously public. It’s the difference between interpretation and perception, reception and representation. Sometimes it can be disquieting for the viewer, because he or she is confronted with something that is simultaneously universal, but very intimate. There is a kind of darkness to some of my pieces. But hopefully the viewers will look at them with a good sense of humour, because I don’t take it too seriously either. I like to play around. L.K.: Coming back to your work at MoMA, what is the methodology that is applied to the education programme? Do you have certain audiences coming to lectures, or is the education process organised in different ways? G.S.: We have any kind audiences of any kind you can imagine. I work with individuals from 6 to 106 years old! Generally speaking, the programmes are divided into age, as well as disability. One programme that we started in 2004 has been a kind of model for other museums, actually, internationally. It’s the Alzheimer’s programme. We have been using art and visual information as a vehicle to trigger memories, because with Alzheimer’s or dementia usually the longterm memories are the last ones to diminish. So, when individuals see something that they have seen in their childhood or in their younger days, it can trigger a process of recollection. Sometimes they say, “Oh, that reminds me when...” or did something else. So the art is used as a vehicle to exercise those memories. L.K.: The process becomes therapeutic as well. G.S.: Yes, absolutely. And it is not only that the respective individual benefits from it, but also the primary caregivers, who often are their family members. And have his or her own levels of stress, because it is somebody you love. And what are we but a compilation of memories? And when your memories start disappearing and even your mother or brother does not recognize who you are, it can be a very difficult situation to deal with. So this programme and educational process gives an opportunity for the caregivers to relax. We have small groups and we work with very specific images – usually figurative. And we basically have conversations – very casual. There is training involved, of course. Other programmes that we have are for the visually impaired individuals, deaf programmes, kids with autism, etc. Each one requires a certain kind of approach and sensitivity to be successful. We also have professional development programmes, where we work with teachers and art administrators. We use a variety of techniques. What, I think, is critical, is the fact that we use artists. Because artists are really effective in terms of being creative. And that part of the process is really critical towards success, because there is no absolute formula. You have to be able to assess and respond to a given situation as it develops in a very organic way. In that aspect, my work can be seen in parallel, because I work very organically. I just begin and then it grows through a dialogue with the work. I use the same technique in my teaching practice. L.K.: It’s amazing that you have such institutional support for such programmes. It must require a lot of resources. It’s the artists, on the one hand, but you also need the respective specialists on the other hand, who are trained in that specific area and are professionally capable to work with, for example, children with autism. G.S.: Exactly. Because there are specific things that you have to address. Like with children with autism, if there’s too much activity around, it can becomes too disrupting and they cannot focus. I think there is something in the human condition and art is just a tool. For example, I work with students who are unable to talk; they are non-verbal. One student for some reason thought that I look like Jackie Chan. To anybody else I would be like “what are you talking about”, but with that student it was a way we could make a connection. I accepted it. Other teachers were saying that they could not make him do anything, because they were approaching him in a more narrow way. But for us, the dialogue or the connection is where we could begin. This student did an amazing series of vacuum cleaners, only vacuum cleaners, and nobody knew why vacuum cleaners. They were very abstract and very crazy, but beautiful images, the meaning of which nobody really knows. But the images were remarkable, I think Picasso would be proud. Seriously. L.K.: Could you comment of the photos exhibited in the show? G.S.: These photos are portraits of New York City artists with disabilities. This was a project I kind of fell into, because I was taking pictures of my friends. And they said “oh, you should meet this other person” and there was always somebody else I had to meet. So, it was all by word of mouth. And because New York is so dense, there are so many unrecognized artists doing what they do, because they love what they do. To me, it was very fascinating, because the project indirectly talks about a kind of an underground layer of the invisible. It was collaboration, we would meet and talk about whatever, anything that came up – we would get to know each other. And from that point we would begin the shooting. So, they basically dictated the place and how they wanted to be shot, and even when they wanted to be shot. To me it was exactly how I wanted it to be. I wanted the project to be collaborative. It was a book project, so each of the artists was invited to submit a written statement. Some were not capable of it due to various reasons. The range of disabilities was basically anything you can imagine: blind, deaf, autistic, physical and cognitive disabilities. And when you look at these photos, you can see that everybody is included (not all of the works are exhibited in the show in Riga). There is no specific race or ethnicity or economic class – it’s relevant to everybody. It is something that everybody will have to deal with at some point in their lives. Some of the submitted statements were amazing. I did not edit anything, including typographic mistakes, because to me – these were their own words. I did not change anything, I just printed them in the way they were sent. Some of them spoke more about themselves, some people spoke about politics. The project is available online. Some the statements are really remarkable, I found them very informative, but I did not include any of them in the show upstairs. L.K.: And why? G.S.: Well, if I did, I think it would change the content of the work. First, because not everybody has a statement and then I would have to select which statement I want to include. Second, the words are so personal, too. L.K.: Back in New York, when you were approached by cu rator Marina Goldena with the idea of organising an exhibition and teaching session in Latvia, how did you feel? Had you been to Riga or this region before? G.S.: No, this is the furthest in Eastern Europe that I have been. One of the things that I find fascinating about Riga is the architecture, because it’s so eclectic, it shows theā, this is a wonderful opportunity to experience something like this. I find the people to be very nice. I feel like in some ways New York is very abrasive, loud, aggressive. It’s nice to visit, but sometimes it can be very annoying. L.K.: What’s the project you are working on currently? G.S.: Right now I’m just working. I’m in the process. Like I said, I work on a lot of different things simultaneously. I have some pieces on the studio wall, as well as sculptures. I don’t have anything specific in the calendar. L.K.: But what’s the usual procedure? When you feel like your work is completed, do you get in touch with curators? G.S.: No. I just work and hopefully people contact me. I just work. Some of the pieces upstairs are actually more like prototypes of series that I am continually developing. Because I work in an organic way, the work grows as I grow as an individual. I almost never get to the point when I feel like “I’m finished”, I just keep working. (1) www.blurb.com/assets/widget.swf?book_id=2029877&locale=en_US&mode=bookshow | |

| go back | |