|

|

| Oleg Kulik’s life after death Santa Mičule, Student, Art Academy of Latvia | |

| This October the works of the legendary Russian artist Oleg Kulik (b. 1961) were on show in two exhibitions concurrently: Nakedness at the Mūkusala Art Salon and ...for an occurrence to become an adventure... at the Riga Art Space. On the afternoon of 10 October the artist himself presented a speech performance The Red Gratitude, organized by curator Ieva Kalniņa at the cinema KSuns. This autumn 15 years will have passed since Kulik’s first performance in Riga called Two Kuliks. This became a life-changing event not only for the artist himself, but it also had a major impact on the Riga art world, as the audience who had attended the performance were profoundly affected and continued to refer to it as a particularly significant artistic experience long afterwards. As artist Ernests Kļaviņš once said in an interview: at that time in Riga everyone liked Kulik, even those “who paint flowers”. On this occasion also, the artist’s visit attracted a lot of public attention, a testimony to his importance among the local art crowd. So much so that the public tolerated and were even happy about Kulik throwing tomatoes at them as punishment for the inability to create, over these last fifteen years, a better country than the one that we separated from (though it’s unlikely that the real culprits were among the audience). Two Kuliks in 1989 was one of the last performances in the artist’s career, and it almost became his very last artistic production altogether. During the performance Kulik gravely injured himself, yet they were able to save his life; however, if we are to believe what the artist himself said (“I died and was resurrected in Riga”) this event killed him (transformed him) spiritually, opening the way to a completely different awareness of himself and the world. Even though the image of the mad man-dog has been silent for almost fifteen years now, its shadow accompanies every Kulik project. Evidently, the public holds that the noisiest period of the artist’s creative career is the main reference point for evaluating his further creative activities. The shift from body performance to less aggressive and more conventional artistic means of expression is still considered by many to be the end of Kulik’s career. However, on taking a closer look at the works he has created in his post-performance period, we find that the basic ideas have remained unchanged, and instead we have to speak about changes in the outward expression of Kulik’s art. Today it is difficult to define Kulik’s art as belonging to any particular movement of contemporary art, but his performances in the 1990s also were characterized by a wide range of aesthetic strategies: from psychologically deep symbolism to post-modern cynical parodies of both social and institutional critique, never entirely subscribing to any single one. | |

Oļegs Kuļiks. 2013 Photo from the private archive of Oleg Kulik | |

| Oleg Kulik’s photo montages mark the first significant deviation from (and simultaneously an extension of) his public performances. In his series The Russian Style (1999) Kulik still used the image of a dog, and in the compositions we can observe a satirical treatment of the Slavic identity, its clichés and paradoxes. Previously, Kulik provoked reality (the mythical, the social and the economic) with certain actions in public and the mass media, but with his photo montages, however, he attacks with stories. Photo manipulations dominate his art also in the works of the years following. The photograph series Windows (2000–2001; Kulik represented the Yugoslav pavilion with this at the 49th Venice Biennale), Slogans (2003), The Nature Museum or the New Paradise (2000–2001) and other pro- jects mark the artist’s return to the motifs of transparency and reflection, something he was fond of already in the 1980s when during his national service he worked with glass, and later created objects with geometric cutouts from organic glass. Transparency is one of the central categories in Kulik’s aesthetic. It fascinates him not only because of the optical effects, but also as a symbol of a certain worldview with a diversity of meanings, through which it is possible to highlight various forms of interaction between the human being and the surrounding environment. The concept of transparency also relates to Kulik’s zoomorphic performances – seemingly different artistic expressions are united by the at- tempt to incorporate reality into art in the most direct way possible. In his interviews, Kulik has often emphasized the necessity to work with art media that do not transform or obscure reality; initially, his body was used as such a medium – a natural component of the real world. In the context of Kulik’s artistic strategy, the return to the themes of transparency and glass can be viewed as a conversion to a more complex language of images and motifs, where the brutal directness of the human body is replaced by more allegorical messages and cultural-historic references. One of the most expressive confrontations between life and death, reality and illusion, nature and culture, in Kulik’s works can be observed in his works The Nature Museum or the New Paradise and Windows. The compositions with stuffed animals and natural landscapes, where the human images have been reduced to reflections and look far less “alive” than the lifeless animals, renders manifest the idea about the return of the human being to nature, or (according to Kulik) a return to paradise. The viewer also is allowed symbolic access to this paradise at that moment when their reflection can be seen on the glass of the photograph they are viewing. In parallel, this reveals the romantic side of the artist, who in his works strives to achieve utopian unity between the real and the idealized world. Away from Oleg Kulik’s private mythology, the theme of transparency is also a reference to the general conventions of depiction in visual art – a reference to the mutual relationship between physical and tangible reality and its artistic portrayal in the broader traditions of art history. By separating between the traditions of realism and so-called hyperrealism, Kulik is undoubtedly one of those who in their art strive to overcome the superficial forms of things and to reach for their invisible, metaphysical essence. Art historian Ekaterina Degot points out that this trait places Kulik’s art in the Byzantine tradition of depiction, as opposed to the mimetic canons of Western art. Yet another pair of binary oppositions, and another parallel with the performances of the 1990s which also, inevitably, are to be interpreted as a clash between the cultures of the East and the West. An even more radical confrontation can be observed in the series of wax figures entitled Museum (2003). Remembering the stuffed animals which played a large role in Kulik’s previous works, the taking up of taxidermy of human bodies seems to be an ironic gesture which again is a reminder of his 1990s works – a proclamation of the animal as the highest alter ego of the human being, a denial of an anthropocentric worldview and a return to the natural human state by reanimating the animal within ourselves. In this series of hyperrealistic sculptures the human is reduced being to the same sort of museum exhibit as the stuffed animals – and this is an ideologically crucial solution to the conflict between the human person and nature according to Kulik’s artistic worldview. The detailed work of the figures in Museum contrasts with the obvious stitches on the “skin” of the bodies: yet another way of challenging the generally accepted relationship between art and physical reality, pointing out the blurred and often grotesque boundaries between the two. | |

Oleg Kulik. Madonna. Installation. 2013 Publicity photo Courtesy of the artist | |

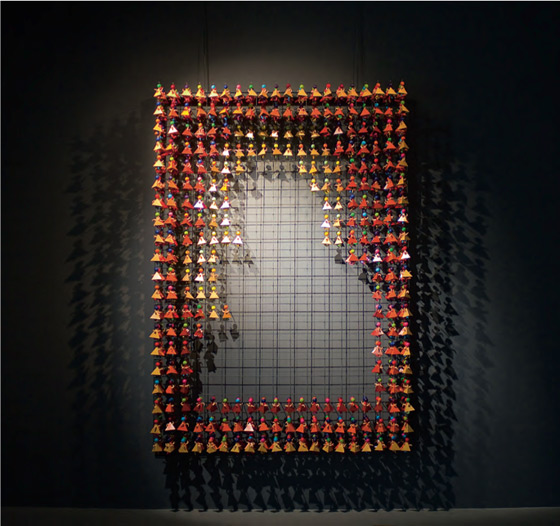

| After longish breaks and spiritual searches in the East, Kulik turned to the contemplation of sacred motifs, not only as an artist, but also as a curator, producing, among other things, the exhibition of Russia’s contemporary art superstars I Believe, which was held in the Moscow art gallery Regina in 2007 and received mixed reviews. One of the most unexpected turns in his career, however, is Kulik’s staging of classical music. To mark the centenary of Sergei Diaghilev’s Paris tours, Oleg Kulik was invited to direct Claudio Monteverdi’s oratorio Vespro della Beata Vergine (Vespers for the Blessed Virgin, 1610) at the Théâtre du Châtelet, the second largest musical theatre in Paris (the opening performance took place in 2009). In truth, Kulik’s participation in the audio-visual genre is no great surprise, given that in his youth he actively participated in amateur theatre, both as actor and playwright. Elements of the theatrical have been present in many Kulik’s works, especially in his legendary curatorial projects of the early 1990s at the gallery Regina, where he experimented with non-traditional ways of displaying artworks, getting carried away with the exhibition space as an artistic category open to multiple interpretations. This enthusiasm is also evident in the so-called reflection works, but its culmination is the visual rendition of his performance of Monteverdi, which Kulik himself has called the first “spatial liturgy” in the world. Owing to the deployment of active video projections, custom designed costumes, acrobatic choreography, and unusual light and scenography effects, the religious musical composition without plot was transformed into a dynamic multimedia spectacle. In other words, the musical experience was significantly enhanced and filled out by the visual effect. Despite widely divergent reviews which veered from a standing ovation at opening night to peevish art critic accusations of being unmusical kitsch, the production once again testified to the fact that Kulik’s creations rarely leave anyone indifferent. It may be a coincidence or not, but the impression left on the Parisian public by the liturgy Kulik directed could be compared to the ballet performances staged by Diaghilev himself and considered shocking in his time. Predictability has never been the artist’s strongest side, and almost every new project has caused confusion. His latest exhibition Frames (2013) at the Regina also turned out to be controversial. The five works on display were united by either a visual or conceptual connection with the theme of ‘frame’. Kazimir Malevich, traditions of the Russian avant-garde, Tibet, Pussy Riot, an icon of Mother of God, neon lights and mirrors – all of these created the semantically oversaturated narrative of the exhibition, where social activism overlapped with a metaphysical feeling of religion and perfectly designed forms. The artist himself interprets this as a new period of transparency in his creative output, only this time it is spiritual transparency, symbolized by the motif of eternity contained within the frames. Frames marks two significant changes in Kulik’s artistic language: the outward form and plasticity of the works has become more important, but the messages of the works have become more abstract and harder to read. The world changes, society changes, Oleg Kulik changes as well, but his distinctiveness has not diminished – in the Western cultural space he is still considered to be a symbol of Russian contemporary art. In terms of his iconic popularity he could be compared to Ilya Kabakov, who for the last few decades has maintained the status of being the best known and most highly rated Russian artist. Many consider Kabakov to be the most influential presence in Russian contemporary art, with the works of post-conceptualists occupying a prime position in the art market. Kulik’s influence in present-day Russian art, on the other hand, has moved in a different direction and has had a powerful impact on politically conscious action art. Present-day artists’ gestures of protest have become more radical, escalating also the reaction on part of the authorities: “incorrect” artworks are brutally removed from exhibitions, both curators and artists are being sued in criminal court, and young women are put away in high-security prisons because they have sung a prayer incorrectly. See how radically different are the paths of succession of the two most famous Russian artists. The extreme political climate of Russia unavoidably divides the representatives of culture into those who are friends of the authorities and those who are adversaries (for example, artist Anatoly Osmolovski, who gained fame with his political provocations in the 1990s, and who now openly declares himself to be a Putin artist). Oleg Kulik emerges out of the murky waters of cultural politics with slogans of pure and impartial art, and emphasizes that the representatives of political action art should seek refuge from politics in aesthetics, as has been done, from Kulik’s point of view, by the members of Pussy Riot. Kulik’s stance should not be viewed as a passive attitude, rather it corresponds with the utopian maxim that “beauty will save the world”. And - who knows, maybe in the latitudes of Russia it really will miraculously save something. Translator into English: Vita Limanoviča | |

| go back | |