|

|

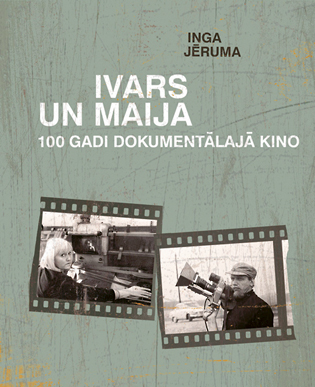

A NOVEL BASED ON THE HISTORY OF FILM A NOVEL BASED ON THE HISTORY OF FILM Kristīne Matīsa, Film Critic About Inga Jēruma's book "Ivars un Maija: 100 gadi dokumentālajā kino" (Rīga: Neputns, 2009.) | |

|

The first emotions to register after finishing reading Inga Jēruma’s thick book Ivars un Maija. 100 gadi dokumentālajā kino are – oddly, perhaps – joy and relief. Firstly, because finally a solid foundation stone has been laid for the grand edifice which, as yet unbuilt, weighs heavily on my own conscience, and hopefully that of some other Latvian film chronicler, researcher or historian. I’m speaking of the history of documentary film in Latvia, which has long deserved thorough research and the thickest of tomes. Besides, the time approaches when evidence of this history will only be provided by documents and archive materials, not living witnesses. So it is especially fortuitous that the era of Maija and Ivars Seleckis has been captured while still alive and active – and thankfully Maija has worked not only on Ivars’ films, because through her the book touches on Herz Frank, Aivars Freimanis, Ansis Epners and other congenial colleagues, recording them also in written history. Admittedly, the choice to end this era with Operdziedātāja uz skrituļslidām (‘Primadonna on Rollerskates’, 2002) seems somewhat random and nonconceptual – I do understand this has been dictated by the lengthy time period over which the book was put together, however, perhaps it may have been more logical to stay within the boundaries of the 20th century. Secondly, purely professionally I am overjoyed by the seemingly elementary (chronological), yet very constructive structure of the book that makes it significantly more substantial than the usual collections of trivia, which similar memoir-based creations can often become. | |

Inga Jēruma. Ivars un Maija: 100 gadi dokumentālajā kino (Ivars and Maija. 100 Years in Documentary Cinema). Rīga: Neputns, 2009. 464 lpp.: il. | |

|

Ivars’ famous notebooks, which I had only heard of before, but now have seen, purposefully used just like Maija’s diaries used in moderation and in the right places, these authentic texts, along with minutes of meetings and other documents from the Arts Council, supply the lively narrative with a strong and, most importantly, believable framework. Of course, it is only natural that in places where the reminiscences are not supplemented with documentary notes, things may fade or change (for example, the soon-to-be-published book on the 20 years of the Arsenāls film forum will feature a slightly different account of Arnolds Plaudis’ and Augusts Sukuts’ run of three kilometres in eight minutes), but the authors have cleverly used even this shortcoming, so characteristic of memories, to the book’s advantage: for example, Mikhail Shneiderov’s and Mikhail Poselsky’s stories about each of them filming the dead body of Hitler are followed by a warmly ironic comment: “Be that as it may, but they both really were in Berlin at the time.” The book is made even more valuable by its carefully crafted section of appendices – first of all the “gallery” of posters for Ivars Seleckis’ films, noteworthy not just as creations by brilliantly talented artists, but also as a wonderful testament to the changeability of the world (for example, the title of the first Šķērsiela (‘Side Street’) film is translated into Russian on the poster, while the poster for the later Jaunie laiki Šķērsielā (‘New Times on the Side Street’) is also in English). Similarly, an entire scene from an era is conjured up by a short sentence from Ivars’ diary, written in December 1987 – the film studio car is late because it has spent an hour queuing for petrol (p. 318) Another very important compilation is the vast filmography for each of the two protagonists (Maija’s even turns out to be the longer one!), and my main source of joy here is the respect shown to colleagues – the entry for each film also lists the other members of crew (with the peculiar exception of Uldis Brauns’ feature length film 235 000 000 – didn’t the anonymous “six cameramen” and the unmentioned co-directors deserve to see their names on this list? If only for the reason that there are very few publicly available sources which can provide full credits of this culturally and historically important film.) The little list of people in charge of the cinema process in Latvia is completely unique, requiring a great deal of work to compile this information, however sometimes it provokes amusing reflection – for example, why is it that film studio director Heinrihs Lepeško managed to firmly hold on to his chair for 20 years, while during the same period the managers of the newsreel department never lasted more than two years in their posts? Small addendum: the “lighting technician” and “the other lightning technician” in the group picture from the film Eduards Ševardnadze. No pagātnes uz nākotni (‘Eduard Shevardnadze. From Past to Future’) (p. 359) are Uldis Deičmanis and Viktors Randars. So that the review does not turn into an uncritical panegyric, I will honestly admit that quite personally I was not overenthusiastic about some of the things in this book. For example, there is the humanly understandable (because the grass is greener and cinema is better in your youth), but not quite objective notion discernible between the lines of the text – especially in the final part of the book – that true filmmaking, “Great Latvian Cinema” could emerge and emerged only at the Riga Film Studio, and after its demise only “some greenhorn directors will try to make cheap little short films of undergraduate quality” (p. 407). It is very odd that this is said by Maija – it could perhaps be expected of Ivars, who is, of course, a recognised master of epic feature-length documentary cinema. But we shouldn’t ignore the fact that one of the brightest pages in Latvian and world film history is Herz Frank’s “little short film” Vecāks par desmit minūtēm (‘Ten Minutes Older’), which was probably not very expensive either – a single camera, a couple of spotlights and 282 metres of film… Ironically, Ivars’ pronouncement that 52 minutes is a “not very long” for a documentary (p. 366) was reaffirmed by this year’s Lielais Kristaps festival, where each of the entries nominated in the best documentary short category was five times the length of those ten minutes that were once so precisely, meaningfully and amply sufficient for any of the classic masters, including Ivars Seleckis… Another debatable question is the matter of the demise of newsreels, a subject discussed several times in the book, and one which the couple naturally mention with regret. It could, however, be argued and perhaps even proved that in this age of exceedingly fast information circulation the newsreel is unfortunately an archaic format that has exhausted its possibilities. Therefore the emphasis of the dispute should be shifted to the necessity for visual documentation, not just newsreels as the only possible manifestation of this kind of documentary. And another nuance, perhaps even unrelated to film, which surprised me in this “love story”, as it was called at its launch by the editor, Inga Pērkone: I am no militant feminist, but whilst reading the book I gradually found myself becoming more and more irritated by the pronounced patriarchalism and the the dominating male chauvinism in the relationship. Maija is revealed in the book as a clever and talented individual; I am in complete agreement with Miks Savisko who considers her to be the “mother” of the famed Riga documentary cinema, as it was she who edited the majority of the “golden collection” films, and as a film editor “brought up” most of the young men who later became recognised classic directors. This book is not merely a dry account of film history, it is an emotionally and expressively rich novel. It is truly worthy of the eight years that Inga Jēruma, together with Maija and Ivars Seleckis, have devoted to its creation. /Translator into English: Līva Ozola/ | |

| go back | |