|

|

| A Woman Takes Little Space Zane Oborenko, Culture Theorist Conversation with the artist Liin Siib | |

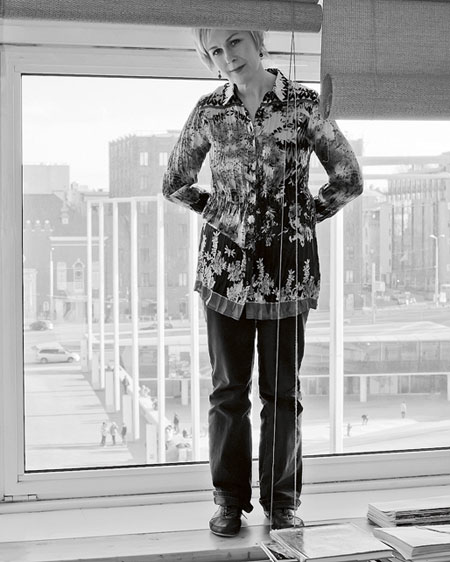

Liin Siib. 2011 | |

| Zane Oborenko: At the Biennale you will be representing Estonia and within your project – Estonian woman. But since Estonia hasn’t got a very well known international identity, neither does Estonian woman. The viewer is just about to get to know her… Why were you interested in her? Liina Siib: For the last few years I have examined and dealt in my works with several aspects of being a woman. Why I made this particular project A Woman Takes Little Space was a debate in Estonian media about the inequality between men and women in Estonian society; it started with the discussion that women live much longer than men and ended up focusing on the gender pay gap. It is quite wide, the biggest in the European Union. Women receive around 28% less pay than men. And it’s a mystery, nobody knows where it comes from, why it has happened, and it’s not only because of maternity issues. In comments about this topic I was surprised to read that women could stay at home, should earn less, and in general are used to taking less space too. So I decided that now I will go looking for a woman who takes up little space and I did. I took my camera and went out to look for her. It was very purposeful. Z.O.: Is it possible to identify Estonian culture through her? Is the term “Estonian” relevant at all in the context of your work in Venice? L.S.: I don’t put the emphasis on the word “Estonia” here; I have the same types of photographs from China and Germany as well – a woman in restricted working conditions. But as most of the photos and videos originate from here… so the location and mentality plays its role. The space is Estonian space, and perhaps there are some similarities of this kind of mise-en-scene with other former Soviet Union countries. I don’t stress on the nationalistic aspect, quite many of the women I’ve been photographing are Russian-speaking. I don’t draw a border between Estonian and non-Estonian communities, but of course there is a border… Z.O.: We can say then that it is not a work about Estonia, but rather a work from Estonia. What does it mean to work in Estonia? L.S.: Yes, that’s correct, that’s the geography, the space and perhaps the local mentality, patience with conditions. Maybe it’s my becoming more aware of where I’m living. I have been photographing here since the mid-1990s. I was looking for interesting spaces and locations, and trying to do interesting works, but I was not thinking so much of connecting the social background with the individual, although it has been present in some photographic series from the very beginning. I was not so aware of it, it just happened to be there. Now I try to think more of possible meanings and of what I’m doing. This is also the reason why I’m working with Estonian matters right now. I’m from here. I know this place better, but you can never know enough. | |

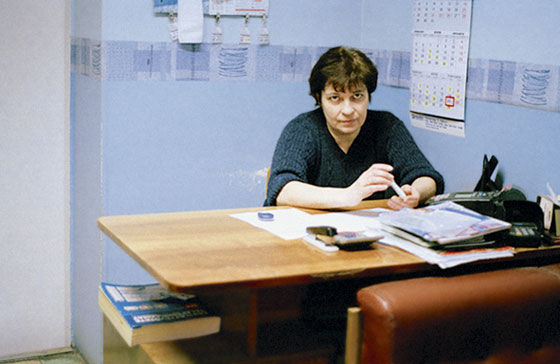

Liin Siib. From the series 'A Woman Takes Little Space'. Digital print. 30x45 cm. 2008-2011. Courtesy of artist | |

| Z.O.: There are some places that don’t allow you to become part of them. L.S.: I had this kind of experience in England when I studied and lived there. I always felt a stranger, but it was fine because I was not attached, and for doing a film and photo project it was OK. But I couldn’t do the kind of work I’m doing now anywhere else but in Estonia. It would take much more time and effort to get so close to the people, to really address them, to ask their opinion. It’s more accessible here. For me it is important to know what is happening to the people I photograph and to talk to them. It isn’t just going and taking the picture. Perhaps I have a couple of pictures like that, but mostly I want to talk to people. In a way, it deals with my own identity as well. For me as a person living in Estonia it is important. When I was a child here in Soviet times, there was a big Russian-speaking community and an Estonian-speaking community and we never spoke to each other, the children hardly ever were on the same playground. I think there were places where it was possible, but where I was growing up it was just living together, side by side, without interaction. This is strange. And it is also something I try to free myself from. It feels odd living in one country and not knowing about each other. It is also interesting to see how the media are representing different ethnic groups in Estonia. It’s always done in the same way, with the same approach, but there are so many different layers which are interesting. Russian-speaking women from different ethnic groups bring here a different joy of life, different manners and different ways, and I think it’s important to have these differences. Also, to compare them with contemporary Estonian women and their way of life. Z.O.: The national essence in the arts has lost a great deal of its charm, but the Biennale di Venezia with its national pavilion system keeps the tradition of the national divide still alive. What importance does it have for you and how does it influence your work? L.S.: For me representing Estonia is not a very easy task. It is a big responsibility to do something and not bring shame on Estonia as a country and on its art scene, and also to be interesting, to attract visitors, to show them problems that we are dealing with, open up their ideas or interest. It’s not like a tourism office, of course… When visiting the Biennale in 2009 I thought about its country-based representations – it’s true, it does not make much sense anymore. Representing countries makes me think more of sports competitions. For me art is not a sport. But the reason why I wanted to participate was to gain more time for my work, to make my project and to develop the themes I’ve been working on. Z.O.: The Venice Biennale is a part of the representational world in which we live in. How can artworks be made the objects of encounter, not of recognition, and how is it possible to think about art in a non-representational way? L.S.: When I’m doing these photographs, for me it is important to represent an encounter, rather than just another image of a woman. I don’t know how to achieve it really, but I try, consciously. I do several photo shots and then I choose the one that I’ll use. It should be something more than just a click, it shouldn’t be journalism. And I don’t want it to be art, either. I want it to be about a woman, the way she lives and works, rather than showing her as an art object or model for the artist. Of course, this element is always there, but I try to get rid of it and this is, perhaps, why I use ‘neorealist’ ways. Nothing is staged for shooting. The scene should be there already or happen on the spot. The people being photographed play themselves. But I’m not sure if the viewer will have the same feeling of encounter. I also try to photograph only the women who spark in me some kind of memories, or the image of the woman I see intrigues me, somehow it’s not just another woman. | |

Liin Siib. From the series 'A Woman Takes Little Space'. Digital print. 30x45 cm. 2008-2011. Courtesy of artist | |

| Z.O.: There is a trend/wish to avoid narrative in contemporary art, are you trying to get rid of that too? L.S.: I wouldn’t say that I am trying to get rid of narrative, but I try to get rid of artificialness, of the academy in myself, the knowledge of how to make art and take photographs, compositional rules and things that are always there, saying what is a good image and what is a failure as art. We already see the image, coming from our art education background, and this is impossible to get rid of it completely, but still, somehow, I try to think about it. There is a thin line between documentary, journalism and art, and I try to be in between them, but I’m not against the narrative at all. As Susan Sontag says in her book On Photography: “Only that which narrates can make us understand”. Z.O.: Through spectatorship there occurs a process of multiplying the points of view that introduce infinity in representations, but does the work of art still maintain a unique centre, which gathers and represents all the others? Is there some kind of common social consciousness in the arts? L.S.: I think that there is, because when I’m doing art it has my own experience of life, but on the other hand all this information is coming from everywhere right now, so there is no innocence in this sense. Besides, the context of the art that we are creating is changing so fast. Every day one has to define what is going on and what one can do about it. This notion of the artist sitting in an “ivory tower” and making genius art… perhaps it’s possible, but I’m not interested in art like that. I’m interested in knowing what others perceive through my works. I think that there is one thing that I see from my point of view, but there is a point of view that the work itself creates during the process of its making and while on display, something that others can see. If they talk about it to me, it’s even better. Then it also becomes an interaction where I can perceive my work differently. I have noticed that there exists sometimes a difference between how men and women perceive the same work where the subject is a woman. Z.O.: In works of art in general there is a tripartite division between reality (Estonia), the representation (artwork) and the author (subjectivity). But in Venice you might also have to take into consideration many more things. L.S.: Yes, of course, Venice is another space, and Palazzo Malipiero is yet another one and I think: how will my work be perceived there, in that context? Not everywhere in Europe women are so occupied by their work; they have a different relationship to it…to society. And I know that the Eastern European label is also there, not perhaps memories from Soviet times any more, but there are such connotations that always come up with this kind of presentation. Somehow the Italian link is important for me, because I’m a big fan of Italy, its people, neorealist films and food, too. Z.O: And Tintoretto? Did Bice Curiger’s focus on this painter influence your work? L.O.: I like Tintoretto’s paintings, but it didn’t influence my work, because the raw material of it was already there. But, to my big surprise, I found out that the types of women I’m portraying are similar to Venetian women. However these are rather coincidental similarities. Z.O: Are the issues of representation important to you? L.S.: They are important, of course, otherwise there wouldn’t be any of these works. I was just writing a paper on how I became an artist working with photography and I thought about representation and installation, that it’s something to be studied a lot, and also how to deal with form. Often you have a good idea, but how to find the form for it? And representation, in a way, comes out of this: representation, rhetoric, form. In photography rhetoric is very important, what is the context of the photographic image and so on, it’s endless. The more I get to know about things, the harder it becomes. Knowledge somehow can hinder representation. When one does this, one knows how people will receive it and if one does that, they will perceive it differently. It’s like a chess game: one just tries to find an optimal way of representation. But when taking photographs one also depends very much on space, location. Since I’m not staging things, I’m dependent on what is available there. It also influences the outcome. | |

Liin Siib. From the series 'A Woman Takes Little Space'. Digital print. 30x45 cm. 2008-2011. Courtesy of artist | |

| Z.O: You are well known for digital manipulation of your pictures, but in these series you are avoiding doing that. L.S.: Everything is on film. I work with an old Nikon FM camera, I make tens of pictures to get just the one image. Actually, I had one rule while photographing these women – these pictures should not be portraits, rather they are about a woman in the space. Although I know their names and I know where they work, it’s not representing them as Ludmila or Maria, but it’s representing them as a woman in the space. Z.O: According to O’Sullivan, with the arts we expect “our typical ways of being in the world” to be “challenged, finding a way of seeing and thinking this world differently”. L.S.: I try to make visible the layers and things in our environment and society that are not much exposed right now. Maybe in Soviet times the working woman was presented as a heroic woman undertaking a heroic deed, pictured from a low angle, but no-one cared what happened to this woman actually. Contemporary media is full of images that represent a woman either as a whore, a good mother or a keen consumer. For myself, it’s interesting to find new ways to show the phenomena that are not so visible or self-evident. Z.O.: How can someone be distinguished as an artist or non-artist? L.S.: The more I do art, the less important for me is the question about borders between art and non-art. When I’m doing my work, I’m not thinking that I’m making art. Z.O.: But the difference can be of great significance in the consequences that the (art) work has. The example of the scandal surrounding Carine Roitfeld, the former editor-in-chief of Vogue France, is a good example if compared to your artworks Scratch Drive and Presumed Innocence, where as in the Vogue editorial Cadeaux (‘gifts’) young girls were dressed up like adult women, plus they were photographed in settings that sexualized them. As a result, Roitfeld lost her job. L.S.: That’s true, this is what I wanted to say. As an artist I can do similar things, but if I were to be a journalist or whatever, social worker, I’d be fired on the spot, because there are very firm rules about what can be represented, and how things should be represented. Art is loose enough to give space where one doesn’t have to abide by the rules that characterize advertising or other profit worlds. An artist can make his or her own rules. Of course, there are ethical considerations that one ought to follow. This “losing innocence” or playing with the theme of innocence is also very interesting. Right now I’m not doing this kind of work, but ten years ago one of my photo series, (Name Changed), got really bad press reviews because people perceived it as a real event, yet it was an artwork about child abuse and it was all completely staged. Even the designer of the exhibition came to me and asked: “How did you get to see these things?” The very sad problem is that we never get to see these things, or even if we could, we would choose not to. But art is there, it might sound banal, but it’s there to test the boundaries. Not just for the sake of scandal; when I did the work I didn’t think it would create any scandal or that there would be this kind of reaction to it. If I’d known, I’d never have done it, for me it was a shock in a way. I think one just wants to make a good work. But there is always present this double thinking. Last summer in our neighbouring town I saw the celebrations for their 30-year anniversary, where young children were presenting a performance dressed up like little courtesans. They were erotic and it was meant to be like that. And it was a public presentation. It’s there all around us, but when someone photographs it, it becomes a problem… Z.O.: And are you a feminist, a feminist artist? L.S.: The older I become, the more I sympathize with feminist literary and art theories, also with theories of gendered space. I test some of these ideas in my works, but what I see is a vast array of differences, a variety of patterns. Individual stories. Being a feminist means a certain political engagement to me, and this is what I am not interested in. I think that the fight for less rigid gender roles should rather be carried on in the home, in kindergartens and schools. Women as mothers and thus educators, in a wider sense, could have their word to say here if they were ready for that. | |

| go back | |