|

|

| The magnetism of Roberts Johansons’ photos Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa, Culture Theorist | |

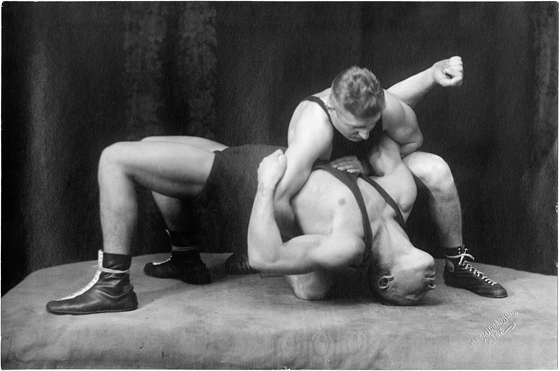

| Roberts Johansons (1877–1959) was a contemporary of Mārtiņš Buclers, Jānis Rieksts, Vilis Rīdzenieks, Kārlis Bauls and other photographers that have been important in the development of local photographic history. This esteemed master of salon photography, author of an invaluable photographic archive and artist with a long list of exhibitions beginning from 1907 which included towns in Latvia and Russia as well as major European cities like London and Rome and even distant New York, he was a fervent supporter of the idea for the establishment of a Latvian Museum of Photography.(1) He was an enthusiastic practitioner of his profession who, with the patience characteristic of a farmer and a reverence for know-ledge, always strove for perfection in the skills of his trade. Among his works there aren’t any iconic images like the burning tower of St. Peter’s Church(2), and his technically perfectly executed works of art confined to the style of pictorialism entirely belong to the time in which they were created. They don’t surprise us with anything in particular, yet the documentary-like archive of pictures that he created in the 1920s and 30s even in today’s context continues to allow us refer to him as one of the more prominent personalities in the history of Latvian photography. My interest in Roberts Johansons and his photographic legacy began in my study years, when I decided to devote my course paper to the following exciting theme: The Photo Recording of Orthodox Churches in Riga up to 1940. My search for photographs and evidence about their origins was crowned by a significant number of visits to the collections and archives of Riga’s museums, where along with images captured by several other authors I regularly came across pictures taken by Johansons. A real treasure trove was discovered at the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation, where I whiled away the hours not only examining the sought after photos of churches, but also, inspired by inquisitive interest, flicking through Johansons’ extensive file of photographs. I was attracted in particular by the focussed determination with which he’d worked. This wasn’t an archive which had come about by chance, but rather a conscious collection of evidence of his time, “historical documents”(3), as he himself called them – an admirably diverse report for future citizens. One after the other, the images, sorted into wooden drawers, brought to light both familiar as well as unseen Riga buildings, and fragments thereof: stairwells, portals, attics etc.; sacred buildings; portraits of artists; staged compositions; salon photos; the faces of residents of the capital city – sorted according to type; country scenes, landscapes and systematically taken pictures of farmers at work; Song Celebration participants; people celebrating Midsummer’s Eve; ship building – the list goes on and on. The albums which the photographer himself put together offer not only beautiful postcards and ethereal portraits for contemplation, but also provide an introduction to famous early 20 century Latvian and Russian athletes. The pictures of these respectfully display handsome men’s bodies with well-developed muscle definition. Beautiful women are not ignored either – the assortment of photos includes nudes, as well as the nylon stocking clad legs of elegant and beautiful young ladies. A huge and captivating legacy.(4) | |

Roberts Johansons. Raiņa bulvāris. In the foreground the Embassy of Great Britain. 1930s Courtesy of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation | |

| The chronicle of Johansons’ professional life starts in 1896, when he arrived in Riga from Aizkraukle municipality, where he was born, and began his studies with the photographer Anton von Bylinski. After three years of study, with a photographer’s certificate in his pocket, the young man headed to St. Petersburg to further his studies in drawing and retouching at the Central Technical Drawing School, named after Baron Alexander von Stieglitz, at that time a popular businessman and patron.(5) He also worked in a number of photo studios where, judging from the entries in his diary, he initially did retouching work. In later years the photographer had developed the skill to such an extent that, while retouching photos, he could free his mind of thoughts completely and even have a brief nap, as his hand knew exactly what to do. If we were to use today’s categories, he could be imagined as a noteworthy expert in the use of Photoshop, one who makes the beauties in the pages of magazines even more beautiful and men’s moustaches and their cigar smoke – even more expressive. Although from a different series, a very pleasing example is the 1930s image of a street-cleaning truck sliding past the British Embassy, where the master, by retouching a negative, has transformed the diffused spurts of water into a drawing of energetic striped jets of water. Johansons returned to Latvia in 1908 with the serious intention of opening his first photo studio. In his recollections, the period up until the First World War was a boom time for photography, marking the rapid development of it as an independent branch of fine art, and giving the photographer’s trade the prestige of a well paid job. Unfortunately, there isn’t much evidence remaining of Johansons’ achievements during this period. At the beginning of World War I, the photographer and his family once again ended up in Russia, this time in its megalopolis Moscow. There in 1916 the photographer and his wife opened a photo salon Venera; he had also been invited to head up a course in practical photography at the Association of Russian Artists. In parallel with his day job, he continued to create new art photos and participated in exhibitions. As he’d always done, he continued to follow art processes with great interest, visiting museums and attending lectures on painting, graphics and sculpture.(6) While in Moscow, during the period from 1920 to 1924 another very significant collection was created by Roberts Johansons – a series of portraits of Russian artists and people employed in the cultural sphere, which was intended to be published as an album (unfortunately this never actually came about). As a valuable addition, nearly every catalogued portrait bears the pictured artist’s autograph, and often an inspired handwritten line about the essence of art, its mission and meaning as well.(7) More than 80 artists were immortalised in many hundreds of photos, among them names which nowadays cause us to tremble with respect: Viktor and Apollinary Vasnetsov, Mikhail Nesterov, Fyodor Shalyapin, Konstantin Korovin, Leonid Pasternak, Sergey Vinogradov and others. The portraits of other authors highly-regarded at the time, but nowadays for whatever reason less well known, or completely unknown, are no less significant. The photographs allow one to gain an insight into episodes of 1920s Russian art history that have already been forgotten in the mists of time, and for researchers to elaborate a more complete overview of this history for the benefit of coming generations. The album materials (with all of the artists’ autographs) are currently held in the collection of the Latvian National Museum of Art. However, one part of the most valuable materials – the negatives – has either perished or is being kept in some secret hiding place, but the other part is stored in Moscow at the State Tretyakov Gallery, which specialists obtained for their collection in 1980 from the photographer’s relatives (grandsons, possibly).(8) In 2005, in honour of the Tretyakov Gallery’s 150 anniversary, the G.O.S.T. Gallery in cooperation with the museum’s Audiovisual Materials Research Reference Department held an exhibition ‘Russian Artists as Viewed by a Photographer. Roberts Johansons. Photography 1920–1923’(9) for the people of Moscow, which was deservedly well-received by art lovers. A small 83-page photo album was also released. | |

Roberts Johansons. In the cobbler's workshop. 1932 Courtesy of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation | |

| Roberts Johansons was a good salon photographer. He knew what customers wanted and fully understood what a photograph should convey to its recipient, to those for whom it would be a gift, and for the coming generations. The business should not cause any unnecessary misunderstandings (for example, in order to prevent scandals and so that families wouldn’t be broken up, in taking group photographs one always had to clarify which lady was the wife of which gentleman, so that she should then be positioned next to him in the relevant pose). It also needed to preserve the preferred level of reality: all relationships had to be settled and on a positive note, and in accordance with the established hierarchy, but the external image – in keeping with the aesthetics of a magazine cover. In this respect the portraits of the artists offered greater freedom of expression, as they were already graced with strength of spirit and beauty, which correspondingly had to be allowed to manifest itself according to the individuality of each personage. One genius can be seen pictured whilst working or with instruments in his hands, as if musing over the plan for the next masterpiece or pointing to the “well” from which the brushstrokes of colour, images and moods are drawn, while another has been photographed against a background of his works; another may be seen thoughtfully staring directly at the viewer, or yet another, quite the opposite – into the distance with a reflective look, contemplatively smiling or smoking a pipe during a moment of rest; yet another – serious and uncommunicative. In the image of each personality the photographer, like a good craftsman, has highlighted their most expressive and characteristic traits. A masterful balance has been achieved in the pictures between the stiffness of the set pose and the facial features of the subject, the lines drawn by the soft light, the angle of the shadow, the chosen background and other details. Often they are somewhat mannered, yet very poetic and good portraits, in which we gain a lot of information about the heroes as well as the era and the author himself (the photographer’s great respect and reverence towards painting can be felt as a significant motivation in the creation of the series). Over the next decades – right up to the 1950s – Johansons added photographs of Latvian artists to his gallery. Among them were portraits of Vilhelms Purvītis, Jānis Kuga, Aleksandrs Apsītis, Ludolfs Liberts, Voldemārs Irbe (Irbīte), Indriķis Zeberiņš, Kārlis Miesnieks and Jānis Roberts Tillbergs. It should be mentioned that with the passing of the years the photos became more and more laconic and simpler. On his return to Latvia in 1924 Johansons started up a new salon. There he received not only clients desiring attractive portraits, but he also invited selected citizens to be photographed for his collection of social types. The master’s model, Matilde Ozoliņa, whilst sharing her memories related that when still a young lady she was invited to go to the photo studio with the aim of posing as a “real folk archetype”. At their meetings, which she remembered fondly, Johansons – whom she described as an elegant gentleman with a cane and an attentive gaze hidden behind a pincenez – had talked a lot and with great conviction about photography as a form of art, and about the importance of the model in the creation of a work.(10) The photographs of representative types which have been preserved to this day also show people in their natural environment: grimy cobblers by the light of a kerosene lamp in the workshop, a blind violinist (Johansons too played the violin), a chimneysweep on his daily rounds and a frontal and profile view of a coachman, a classic portrait of an old Jew, an image of a beggar and others. In almost literary fashion the images tell us about the “ordinary people” of the city. | |

Roberts Johansons. Berners and Salmiņš. 1920s Courtesy of the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation | |

| One can sense sincerity and genuine respect in the photographer’s view of things. Johansons himself came from a farming family, so the working man’s lot was close and familiar to him. (In one of his diaries also the photographer gives a thorough description, based on childhood memories, of the life of a Latvian farmer.) In the pictures, the worn clothing and serious features of the workmen create a dark charm which can be likened to the aesthetic of ruins, and is a pleasant contrast to the salon photo, polished to airy lightness. The gallery of types compiled by the photographer isn’t as conceptually developed (at least it hasn’t been preserved as such to this day) as that of his German colleague August Sander’s (1876–1964) 20 century series of people’s portraits, but in the local context this does not in any way lessen its value. Towards the end of the 1920s and in the 1930s many pictures of Riga scenes were taken with the aim of pictorial documentation, undoubtedly also acknowledging Johansons’ emotional attachment to the city after all those years spent abroad. There is nothing superfluous in these images. It is clear that by using the appropriate technical methods (lenses, direction of light and composition), they were taken in order to immortalize specific objects with the goal of preserving the particular “flavour” of the corresponding period; it is very informative and wonderful illustrative material from a bygone era. Even today, restorers, architects, historians and researchers from other fields use Johansons’ photographs as a guide when reconstructing originals and researching into historical facts. Recently I realized, however, that in the pictures of architecture I am most fascinated not so much by the recognition of changes that have taken place in the cityscape, or any surprising discoveries, but specifically by the fact that at that time too, 80 years ago, Riga on the whole was the same city that it is today. Only now it’s bigger. In a strange way, that’s a good feeling. The more expressive building and urban scenes aspiring to the title of “art photo” also definitely included a human figure in the composition, in an equivalent relationship. Among the photographs there are also many views of Riga which had been taken for postcards. Notwithstanding the development of photographic equipment and the entry of roll film cameras into the field in the 1920s, Johansons, as evidenced by museum inventory recording cards, largely remained faithful to the 13x18 cm photographic glass plate format. The camera, which always required a stand as well, was a heavy but reliable companion in the work. This kind of process provided the quality which the master wished to achieve, but consequently the shot always had to be previously planned, foreseeing the intensity and direction of light, and changes in weather conditions. This significantly influenced the monumentalism which can be sensed in Johansons’ photographs, creating the feeling of a very steady and stable world. Johansons’ notes about the Soviet period are full of gloomy observations and disappointments. The field of photography which he had nurtured over decades had now transformed into a production plant with a monthly plan.(11) Like his other colleagues, Johansons the former photo salon manager had become a common line worker, and all the artistic to-do, the polishing of every shot he’d taken to perfection, had to be put aside in the interests of the mass production which took place at ‘Riga Photo’ workshops. The master was still fortunate enough to experience the beginning of a renaissance of photography in Latvia, taking part in the first post-war photo exhibition in 1957 and an exhibition in 1959 dedicated to the 120th anniversary of photography, for which he received a certificate of honour in the twilight years of his life.(12) As soon as you delve a little deeper into them, Johansons’ photographs – whether they be of artists, sportsmen or typological portraits, a building or a picture of a street – invite you to examine what they’re telling you in an unhurried way. Not only the skilfully developed, perfectly balanced compositions of images and subject matter draw you in like a hook, but to a large degree it’s the photographer’s notes on the edges of the negatives: the names, the year and titles... It was important to Johansons to leave a statement for the coming generations, otherwise there was no point to the work. And I can affirm that the photographer’s legacy, which here has been looked at only fragmentarily, provides a high quality way of spending many engrossing hours for all those who like Riga, or are interested in the history of Latvia, photography and art, or basically – like taking photographs. Johansons’ love of his vocation radiates from the photographs just like a magnet, a love which is exemplified by a pronouncement written down in his diary in the later years of his life: “No sport can provide you with as much joy as photography. Its value lies not just in the absorbing activity itself, but is hidden above all in the immeasurable possibilities for its use. No matter what aims or purposes you may be seeking to fufil, evėry time you will find complete satisfaction. You may regard your camera as a companion for obtaining mementos of your travels and excursions, and the photos you yourself take will always be more valuable to you than any postcards that you may buy. Like a permanent source of happy memories, these photos will show people and things from your own personal point of view, they will always remind you of your relationship with them. If wishing to work towards more serious goals, in photography you will find a power-ful means of expression for artistic activity, an indisputable assistant in your field of work, whatever form it may take.”(13) The author of this article wishes to thank Silvija Voite, specialist at the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation, for her advice and assistance in the selection of photographic material. /Translator into English: Uldis Brūns/ 1 At the end of 1938, Johansons wrote an application to the Culture Department of the Education Board for space to be allocated for a museum, but due to the lack of funds received a letter of rejection. – Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation (hereinafter MHRN), VRVM 129 672, p. 44. 2 A reference to the legendary 1941 photograph taken by Vilis Rīdzenieks. 3 MHRN, VRVM 129 674, p. 49. 4 The Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation received the opportunity of acquiring this material on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the great master’s birth – in 1976, when after an exhibition dedicated to the theme of Riga in photography, Johansons’ daughter Valija Vilciņa, at that time the holder of his estate, approached specialists in the field. As a result of successful collaboration the museum obtained an archive of more than 3,000 items for its holdings: photographs (silver gelatin copies, and work created in bromoil and rubber print techniques), glass negatives, photo albums, documents, as well as the diaries that Johansons wrote in his final years. In these he not only looks back at his life, but shares his experiences as a photographer and retoucher, and provides a wealth of reference material about the development of photography and its technical nuances at the beginning of the century, the Soviet period, and fellow photographers. In 1979 the museum held an extensive retrospective exhibition of the great master’s work. The second largest photo archive, in terms of numbers, is the legacy of works by Vilis Rīdzenieks, which is also held at the Museum of the History of Riga and Navigation. As a consequence of two major wars and their aftermath the photos and negatives by other early 20th century photographers nearly all have perished, except for individual works or small collections. 5 Many Latvian artists studied at this school, among them Kārlis Brencēns, Burkards Dzenis, Jānis Kuga, Gustavs Šķilters, Teodors Zaļkalns and others. 6 Like many of his colleagues, Johansons considered painting to be the greatest repository of the principles of art, and therefore visits to art museums and the systematic study of the major works of classic and modern painters was a significant source of knowledge for the arrangement of visual elements in a picture and in the choice of subjects. (And after all, if an artist paints with colours, then a photographer – in black and white photography, with varying intensities of light). At the time photographic associations had taken on an educative role in photography, publishing periodicals as well, however this did not constitute a professional education. 7 For example, the photo in which one can see the artist Lev Lozovsky (Лев Лозовский) with an affectionate cat in his arms is adorned with this inscription: Пусть давит меня жизнь своими котистыми лапами, я углубляюсь в себя, работаю и забывается всё. (“Though life may be suffocating me with its cat’s paws, I delve into myself, I work, and everything is forgotten.” Dated 13 January 1924.) 8 Присмотрись к художникам. Газета, 31 марта 2005. Архив Прессы. [Look to the artist. Gazeta, 31 March 2005. Archive of Press.] www.cargobay.ru/news/gazeta/2005/3/31/id_2579.html. 9 Русские художники глазами фотографа. Роберт Иохансон. Фотография 1920–1923. [Russian artists through the eyes of the photographer. Robert Johanson. Photograph 1920–1923] (15.04.2005–15.05.2005). For more news about the gallery and exhibition see the home page on the internet: www.gostgallery.com. A small view of the portrait gallery can also be obtained on the private blog http://ziggyibruni.livejournal.com/43231.html. 10 Dimenšteins, I., Vīksniņš, R. At that photo workshop on Aleksandra bulvāris, … Rīgas Balss, 28 Feb. 1987. 11 More about this period: Balčus, A. Dvēseļu inženieri ar fotoaparātiem: Fotogrāfija Latvijā 1940. un 1950. gados. [‘Soul Engineers with Cameras. Photography in Latvia in the 1940s and 1950s’] Foto Kvartāls, 2010, No. 2 (22) 12 More detailed biographical data on Roberts Johansons can be obtained in publications by Pēters Korsaks, a historian in Latvian photography. Selected significant articles: Korsaks, P. Mūžs fotogrāfijā. [‘A Life in Photography’] Māksla, 1978, No. 2,; Korsaks, P. Redzamākie 20. gs. sākuma latviešu fotogrāfi. [‘The Most Prominent Early 20th Century Latvian Photographers’] Latvijas fotomāksla: Vēsture un mūsdienas. [‘Latvian Photo Art: History and Today’] Comp. P. Zeile, G. Janaitis.. Rīga: Liesma, 1985, pp. 73–76.; Korsaks, P. Roberta Johansona fotogrāfijās gūtais atziņu ceļš. [‘Roberts Johansons’ Path to Recognition via Photography’] www.foto.lv/vortals/no-vestures/roberta-jahonsona-fotografija-gutais-atzinu-cels.html. 13 MHRN, VRVM 129 674, p. 42. | |

| go back | |