|

|

| Perpetuum mobile Barbara Fässler, Artist A talk with artist Wawrzyniec Tokarski about his painting in motion | |

Wawrzyniec Tokarski. 2012 Photo: Barbara Fässler | |

| How is it possible to create a never ending dance of lightness, a thinking of continuous questioning and a work in progress in perpetual movement with the most static and material medium in art beside sculpture, that’s to say with painting? In the following conversation, Berlin-based Polish painter Wawrzyniec Tokarski explains his strategies on a tightrope between abstract expressionism and the advertising poster, between visual poetry and critical slogan. Painting lived as a permanent cognition and purification process of covering and discovering, where elements picked up from a totally crazy world of mass media are organized in an always different way, in order to produce constantly new meanings which appear almost magically from the coloured surface... Barbara Fässler: What interests you in the medium of painting, nowadays a quite rare and still traditional technique? Wawrzyniec Tokarski: It has been customary to talk of painting as dead since as long as I can remember, or more specifically since it has been questioned to my face by Joseph Kosuth with whom I studied in the early nineties. Despite this, there is still a lot of work to be done in that genre, even though generally not in the way I am using it. I also don’t think painting is very much outdated, neither is it to be considered a particularly traditional medium in comparison. Everything you use in art gets established by time, so in this context, even after a few years media like installation, video or performance become sort of uniformed. The trump of painting since forever is that it is easier to avoid being literal. In photography, for comparison, it is possible to manipulate the subject, but hard to stay ambiguous while doing that. In painting there are different means to leave the conclusion open to the viewer without being obvious about it. That is how I understand the usage of the blur in the paintings of Gerhard Richter. This is what attracts me most about painting. I may not finish an image, and those white fields allow the viewer to complete it. | |

Wawrzyniec Tokarski. So What?. Acrylic on canvas. 220x220 cm. 2010 Publicity photos Courtesy of the artist | |

| B.F.: I noticed that you practice a very fast painting style with the gestural techniques and dripping that we know from Abstract Expressionism, Neo-Expressionism or even the so-called “bad” painting. Which are your own criteria of what is “good” painting for yourself? W.T.: Having criteria about what is “good” painting is not very good for a start, although it is hard to avoid that, actually. I try, as much as I can, not to pay attention to what could be “good” painting, nor do I try to do “bad painting” as an intentional choice. Neither am I painting especially quickly, I think. In a similar way Abstract Expressionism, even though it looks fast, has never been done quickly. I like to be distracted while working, to gain distance. This going a step ahead and two back again helps me to avoid getting caught in a mantra of repetition and self confidence. What creates the impression that the paintings are fast is their quality of laziness or conciseness. I believe an image is as good as it is simple. On the other hand, chance and confusion are still an important part of my approach… B.F.: Painting may be a clarifying process from confusion to clearness and simplicity? W.T.: Of course, this is one of the aspects why I’ve chosen this medium. During the painting process you actually have time and means to reconsider. This is not possible in an immediate technique, where the product is done in one click. In painting it is necessary to actually progress on it, being exposed to the sometimes tire-some and unpleasant process of clarification. Less is more… B.F.: When I saw your art for the first time I thought that it could be the product of different people, because you apply a wide range of different styles from abstraction to figuration, from graphics to typography. What holds your work together? W.T.: I like to think of it like the whole Universe. It has some boundaries, but it’s endless. I don’t understand why I should artificially limit myself. We have only one life, but all the same we are not limited to one point of view. I prefer to search through multiple perspectives, rather than remain constrained to a straight “one way” road. Everything interests me. Today it might be politics, tomorrow it might be what happens on the moon. I don’t feel obliged to fulfil any duty. B.F.: I meant more the formal aspect than the topics. You use different styles and formal codes, maybe influenced from the history of art. W.T.: Sure, you can see that just as quotations, but also it is altogether impossible to avoid a personal note, therefore I’m not in-sisting on anything intentionally special and recognizable in my art, on any sort of personal signature. Trying to be special is always limiting yourself. Look at Beuys or Warhol, the work doesn’t dissociate itself from the outside world by artistic means, quite on the contrary. I would not even dare to speak about a style or convention. It is completely out of question in this context. | |

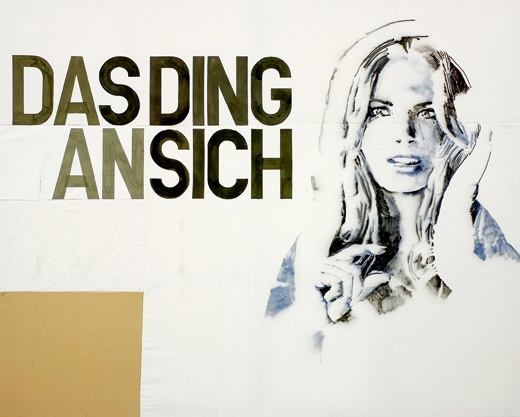

Wawrzyniec Tokarski. Das Ding an sich. Ink on canvas. 240x300 cm. 2010 Publicity photos Courtesy of the Galerie Wentrup, Berlin | |

| B.F.: The issue is more important than the form, for you? W.T.: The content, of course, is essential, the form is only an attribute. On the other hand, you can hardly avoid making a subject of yourself in your own work. This seeps through. As I am unable to experience myself directly, I must try to understand myself through the world, as a mirror, therefore I don’t need to put the accent on myself. B.F.: Another first impression of your works is their huge, almost monumental dimension. Do you look for more visibility, do you want to imitate the effect of advertising in the streets or do you try to englobe and so integrate the viewer? Could you explain your choice? W.T.: Each of your suppositions is a part of the answer. I wouldn’t call the works monumental, because the word “monumental” sounds to me like swearing, it’s something that tries to appear bigger than it really is, while I am trying to stay appropriate at all times. You should consider that the size of an image is always relative to the context where it appears. What I prefer in the bigger format is that it isn’t just a keyhole to peep through, but it becomes part of the scenery, as obvious as architecture. B.F.: I’ve noticed that very often in your exhibitions the paintings are the same height, rather than the same overall scale, to become a sort of “layout” and a regular grid in the space. Do you calculate the exhibition settings when deciding the dimension of a single artwork? W.T.: No, but I try to keep the work modular. It enhances variability and allows rearrangements. I try not to put too many external form variables into the equation, because there is enough diversity inside the paintings themselves. An artist is not an omnipotent objective entity and should have the possibility to reconsider and adopt his work if need be. B.F.: I now would like to come back to the issue of the advertisement. You apply visual and communication methods of advertising, but your message is often ambiguous, not direct or even ironic. How do you construct your images and how do you generate meaning in your paintings? W.T.: Of course, an advertisement has a clear aim to sell you something, but the way advertising is formulated has been changing a lot, even in the last twenty years. An advertisement itself is not free of irony. Actually, I would say that it is not possible to be serious in that world. B.F.: So you think they are not so different in the end? W.T.: I think what distinguishes my work from advertising is that I’m selling something else. B.F.: What? W.T.: If I knew… Every day it’s a different item. B.F.: Do you sell a message or do you sell a painting? W.T.: This question is like if light is made of waves or particles. A message in a painting is manifested in a material way, so, if I am selling a message, I might be also selling a painting. | |

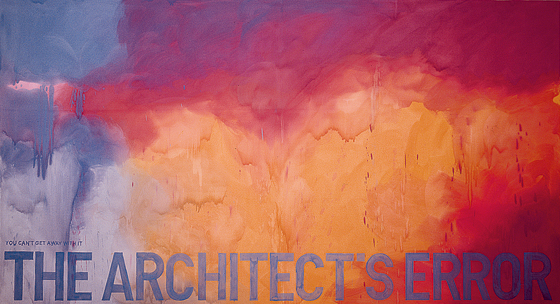

Wawrzyniec Tokarski. The architects’ error. Gouache on canvas. 240x440 cm. 2006 Publicity photos Courtesy of the Galerie Vera Munro, Hamburg | |

| B.F.: What is the relationship between text and image? Could we say that One plus One is Three? A third meaning is generated from the two original elements? How would you describe this mechanism? WT: The sum of elements is usually supposed to be more than just the combination of them. For example, when you build a car, the result is more than just an accumulation of screws and the parts it consists of, because it has more functionalities than all the elements aligned next to each other on the floor. The arithmetic question, what is the sum of one plus one, is also the question of what axiom you choose. I recall a Polish cartoon from the 1980s, a mob carrying statements “2x2=5” which, funnily enough, might be as good a foundation to base arithmetics on as the one we are accustomed to. The problem is that the everyday world wouldn’t be able to empirically confirm results achieved with such a system, making it practically unusable. But science is constantly reinventing its tools to understand the world beyond what is accessible to our bodily experience, and I believe that art has the same right to redefine the tools that are used for its own aims. B.F.: When you speak about contradiction, do you then mean that you are not underlining the meaning of an image with the text in a didactic way, like a caption under a photograph? The text can function as a literal description of what you see in the picture, or on the contrary, the text can open another dimension of meaning, which can produce a sort of tension between the two. W.T.: I understand what you are talking about, but I don’t know if I am consistently and consciously controlling this part in all situations. Generally the text next to an image is supposed to be complementary to it. This means that the image provides some information and the text assists, refines or contradicts that message. While that would be optimal, in the commercial world, for instance, a lot of the imaginary is redundant. Look at music videos, where the music is the subject and the video, usually, is just an addition to it. In an advertisement you will often see pictures whose only aim is just to catch your attention, you know, “sex sells” and the like… B.F.: Normally in the art world there are other rules than in the world of advertising, where you find a very clear aim and communication strategy; even if it’s ironic, the function is defined. In art, you move in a poetic context and the message is more open. I think in your work you are testing those limits, using advertising matters and strategies, then transposed into the art world. Your cutting and univocal messages could also be perceived as a provocation in the art sphere. W.T.: This is why initially I was not into art. But on the other hand, I’m not the first artist addressing those issues. People like Barbara Kruger, who treats art as a communication medium, started her career in advertising. I was never interested in art as an isolated zone from the rest of the world. I do not value it just as such. For me it is a tool, useful for something. For many, art is supposed to be transcendent, but I think this is an illusion. You have to take the best of both worlds. The ‘not accurate’ character of the painted image clashes together with the clear statement of the verb. B.F.: Your paintings are a collage of quotes from our visual and verbal culture. Could we assume that the flow of pictures which is bombarding us through the mass media influences or more precisely constitutes our perception of the world? W.T.: Obviously you cannot avoid that. I think we are partly conscious of this influence, on the other hand we are exposed to a constant flow so much that the most of it escapes our attention. I don’t see the artist as a creative entity, that’s a religious category. By catholic definition, to create means to make something out of nothing. It would contradict the laws of thermodynamics, therefore I’m not going to seriously comment on this. The only thing we artists, among others, can do, in my humble opinion, is to process the existing substance and information. | |

Wawrzyniec Tokarski. The most complete of colors. Gouache on canvas. 300x300 cm. 2006 Publicity photos Courtesy of the Galerie Wentrup, Berlin | |

| B.F.: You often integrate, beside images and texts, some logos into your paintings: those of multinational capitalistic companies are treated the same way as those of humanitarian organizations. Are you declaring by this move that everything is a logo the same way, for instance a Virgin, a Ferrari, a flag or an artwork, and could as well be seen as a symbol, an icon or a cultural paradigm? W.T.: At the end of the day I’m not interested in what is a logo and what is not. I treat the available imagery alike, no matter if inspired by international corporations, states or humanitarian non-governmental organizations. I just want to underline that everything is questionable. B.F.: So could we define it as a questioning of social symbols, considering a Ferrari and a Virgin a “logo” of our culture? W.T.: Of course – the cross, the virgin, the fish, the crescent moon… all that represents something in a given context. We utilize projections everywhere, whether aware of it or not. A drawing of a tree is its projection on the surface of paper. The object becomes the subject and the surface is the context. Generalizations and theories based thereon would not even be possible without abstraction introduced in this way. But here we enter territory where I do not feel very comfortable. B.F.: Now I would like to ask you a more practical question. How do you generate the topics you talk about in your pictures? They cover an almost unlimited range of issues, from metaphysics to reflections on our world, time or chance, and of course about the art world itself. Like in the painting where you write on an abstract expressionist painting, “For further information call +49 (0) 179 50 20 885”, offering personal assistance to the viewer of the artwork. W.T.: I would call my approach pseudo-random. I am just trying to react spontaneously to whatever subject I am attracted to at the moment. There is no system or strategy behind it, as I told you before, I am violently opposed to any system, even if it doesn’t always work out. I try to avoid habits. I try not to set up principles, except to reach targets by the shortest way. Personally I see it as most important to maintain freedom, as far as possible, even if for the sake of contradicting tomorrow everything I say today. | |

| go back | |